by remus jackson, F. Stewart-Taylor, and Cara Wieland

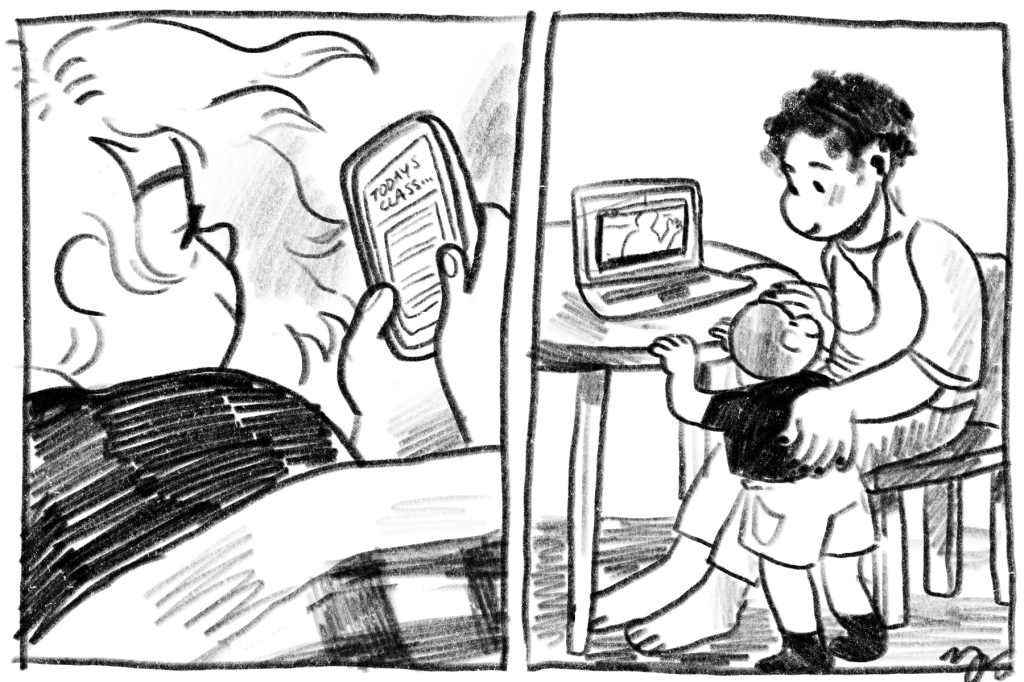

When the University of Florida resumed classes after spring break, we were notified that precautions were being taken against the novel coronavirus. From what we could see, precautions took the form of hand sanitizer bottles left in our classrooms, arriving on the same day as emailed instructions to shift to online learning “wherever possible.” The order to move all classes online followed in a slew of official guidance that had to be revised as the pandemic worsened. However the instructions changed, they accompanied the cheery command “Keep Teaching.”

Advice for graduate students on how to keep teaching was lacking. Creating newly digital classrooms that supported our students, rather than controlling or surveilling them, without relying on videochat technology with serious access barriers for students and teachers alike, required flexibility. This flexibility contrasts starkly with neoliberal “flexibility” requiring us to produce “continuity of instruction” for students in unclear and frightening situations, while frightened and unsure ourselves. As our students scattered, we kept teaching. In order to do so, we turned to strategies learned from mutual aid and disability justice.

Mutual aid comes from communist and anarchist theory and from everyday praxes of survival. The close association between mutual aid and disasters makes it a natural fit for teaching in a pandemic, because extreme circumstances reveal existing gaps and exclusions in social safety networks. COVID-19 has resulted in new coverage, including the Town Hall Project documenting COVID-19 specific mutual aid efforts.[1] However, mutual aid has a long prior history; one example is Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, which includes organizers who have been doing on the ground mutual aid since Hurricane Katrina.[2]

Mutual aid is not limited to disasters; any organizing effort which relies on horizontal and relational organizing to meet needs within a marginalized community could constitute a mutual aid project.[3] Disability justice pedagogy inherently aligns with mutual aid pedagogy. Disability justice is an activist praxis coined by Patty Berne and disability performance art collective Sins Invalid centering “the lives, needs, and organizing strategies of disabled queer and trans and/or Black and brown people marginalized from mainstream disability rights organizing’s white-dominated, single-issue focus.”[4] Disability justice pedagogy prioritizes flexibility and multiple modes of learning to account for individual student accessibility. It is intrinsically adaptable and does not rely on punitive frameworks that exclude or further marginalize students and workers with diverse needs and backgrounds.

The difference between the endless-productivity neoliberalism encourages as “flexibility” and the flexibility we advocate for in our classrooms comes from mutual aid. Disability justice and mutual aid in the classroom reject expectations of ceaseless productivity by reallocating collective efforts to community building and solidarity among students and workers. Mutual aid informed by disability justice asserts that trade-offs won’t always look exactly equal: they are based on the needs of each person, what they’re able to provide, and are conscious of sometimes fluid power dynamics.

Our university’s proposed seamless transition doesn’t account for the fact that students are going to get sick, teachers are going to get sick, people are going to have to care for their kids and sick loved ones; a disability justice and mutual aid inspired classroom does. Our classrooms prioritize student and instructor self-assessment of access needs to design an “already accessible” classroom rather than granting conditional accommodations. Inspired by the care networks of LGBTQ+ disabled people of color which Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha described in Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, we prioritize thinking, teaching, and organizing relationally. Our disability justice pedagogy practices were already designed to listen to students and try to meet their needs as individuals.

As a result of our existing networks, we had some groundwork laid to collaborate on mutual aid for each other as teachers and to extend our disability justice inspired classrooms to this moment of crisis and uncertainty. Our classrooms were already more flexible, less punitive, and more student-driven. We took advantage of our existing community care Discord server to begin sharing resources and checking in with each other—reporting on what tools seem to work, offering each other advice, sharing ideas and offering check ins for mental and physical health and grocery runs.

Before the pandemic, we had already established student-oriented teaching strategies, which largely involve trusting students to know what their needs are, rather than relying on University ‘accommodation’ policies. As Jay Dolmage has argued, requiring students to demonstrate need to the disciplinary standard of the University system punishes students who require accommodation and devalues their expertise about their own needs against non-disabled “expertise” about pedagogy and ability.[5] In the time of COVID-19, trusting students to know their needs is essential. Many of our students had to abruptly move home, including international students; many face limited access to technology or the internet; like us, they’re anxious about their health and the health of loved ones, loss of income, and political uncertainty.

Each of us uses different models for our pandemic classroom structure, drawn from both what we were doing before the pandemic and what fits our students’ and our needs best now. We held conversations with our students in the days before the online transition, asking them what they wanted from an online class and how we could best support their learning, as much learning was possible in these conditions. There is no way to perfectly capture the classrooms we built in-person online, and that isn’t our goal.[6]

Cara was already teaching an asynchronous course online this semester, so the shift post-coronavirus mostly meant checking in with students and relying on a previously instituted syllabus clause that allows three-day windows for each assignment deadline as well as a single-use extra three-day extension to call on if needed with no questions asked. In cases of extenuating circumstances, as obviously has happened for many in the middle of a pandemic, further extensions may be arranged. However, rolling deadlines and a universally applicable extension allow students to plan their own schedules without the requirement of disclosing information that may be intimate or traumatic to express, particularly in the middle of a global crisis.

remus discussed options with their students, and the class decided as a whole to start out with largely asynchronous, pre-recorded materials with the assurance that the format could adjust if needed. This has meant checking their preconceived notions about discussion and classroom community, as this particular group of students already preferred more lecture over discussion, and early attempts to recreate online student to student discussion seemed more stressful to all of us than productive. Working with pre-recorded materials enables them to work at their own pace and prioritize their individual research projects as much as they’re able. Components of the class, such as extremely brief responses to primary materials and a semester long “journal” collecting their notes, were already designed to give them space to get feedback in a less formal way, and now provide a way to touch base on rolling deadlines without adding additional check-in assignments to their plate. Weekly Zoom chats provide a direct moment for students to check in and communicate what they might need to support their continued learning.

Fi has a tiny class, which requested a synchronous option to maintain discussion practices students had enjoyed. To remain accessible to students with reduced internet access or time, there are Zoom sessions for two out of three weekly meetings, and a discussion board to allow students to participate asynchronously, before and after the Zoom calls. The discussion boards enrich Zoom discussions, and content from the Zoom discussions is made available in summary form in the Canvas announcements. Students’ contributions are credited by name. All semester, a summary of class discussions has been posted, with a review of upcoming deadlines and reading assignments. This supports students who could not attend, or who might struggle with note-taking or other accessibility elements of a discussion-based classroom. This is especially true online, when students can lose access mid-discussion.

Flexibility with students empowers them to communicate what they need, whether that’s an extension, additional clarification, or a modification of the assignment. Flexibility also means being willing to reach out as much as we’re able to, and recognizing students often feel they can’t be open with their needs because they’ve been punished or ignored for doing so in the past.

As outlined above, a mutual aid and disability justice approach to teaching under crisis rejects capitalism’s orientation towards constant productivity, exemplified in calls for “continuity of instruction.” The assumption that there can be a seamless transition is an impossible expectation of student and instructor labor. This directly speaks to structural inequities exacerbating coronavirus. The requirement to “keep teaching,” without adjustment or time to rest, is a pretty illustrative example of university teaching job compliance and job compliance valuing profit over life. We don’t want to teach students to work themselves to death over a dollar in someone else’s pocket. Treating Zoom as a one-size-fits-all band aid for this crisis ignores the lived realities of students and teachers who may not be able to access Zoom or who may have disabilities that make virtual conferencing extremely difficult. remus, for instance, has difficulties processing audio which are exacerbated by the Zoom format, and Cara is hard of hearing—certainly not ideal for trying to teach through Zoom.

Continuing to teach means trusting students, believing students, not penalizing or punishing students for missing things, no tiny point assignments to ‘keep them on track,’ and checking our egos as instructors. It means acknowledging that the COVID-19 pandemic is a confusing, stressful, and traumatic time beyond just class or likely inconveniences. We must begin with compassion rather than asking them for proof of their circumstance. Rather than forcing student compliance, we must meet our students in solidarity.

remus jackson is a cartoonist and PhD student in English. Their research explores gender, critical prison studies and museum studies. They’re also the cohost of Drawing a Dialogue, a research-driven comic studies podcast.

F. Stewart-Taylor is a PhD student in English, focussing on comics, visual studies, and small press and self-published work. Currently organizing with the Civic Media Center and Gainesville Covid-19 Mutual Aid.

Cara Wieland is a PhD student in English focusing on disability, postcolonial studies, and museum education. They are also disabled, a caregiver, and #HighRiskCovid19.

Further Reading

[1] https://www.mutualaidhub.org/.

[2] https://mutualaiddisasterrelief.org/about/.

[3] Seattle’s Big Door Brigade offers one definition here: https://bigdoorbrigade.com/what-is-mutual-aid/.

[4] Leah Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), 15.

[5] Jay Dolmage, The Retrofit (University of Michigan Press, 2017).

[6] A previous presentation on the topic of creating accessible classrooms by the authors of this piece can be found here: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1LyjHCU8JgechJTuezSPFvtnWS6GZQ6nO.

Pingback: Discord