by Dr. Rebecca Weber

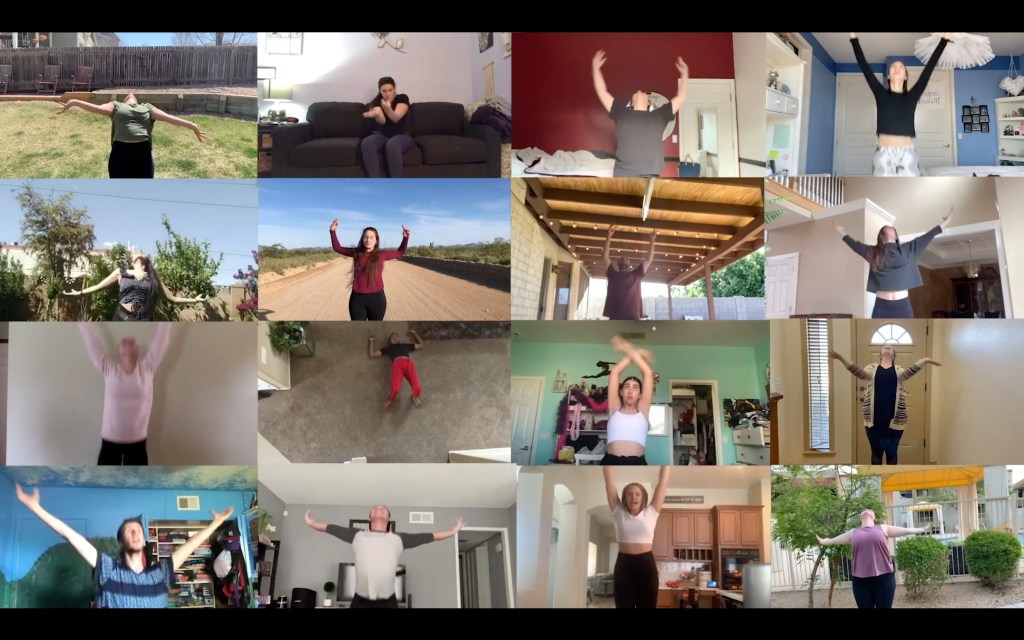

The global COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has caused seismic changes to life across the globe, as localities and entire countries shifted into various stages of “lockdown” and live, communal experiences were forbidden in order to stem the spread of coronavirus. Consequently, dance practice, production, and teaching shifted to digitized methods as live arts spaces closed and countries went into lockdown[i]. At the beginning, there was a sense of collective loss as the field mourned the lack of in-person contact. Dance is a highly embodied art form, however, recently there has been an explosion of activity in “dance tech.” Technology as a medium for creation and connection is nothing new, but dance as a field has been slower to take up digital modes than other realms of artistic practice.[ii] For example, Whatley and Varney[iii] note “the relatively slow uptake of digital technologies” within choreographic practice.

However, despite its slow uptake and the rapid shifts to digital in the field, there is a history of technology use within various dance contexts, including education;[iv] dance creation/choreography and performance;[v] scoring, archiving, documentation, and annotation;[vi] among others.[vii] Technology has even been an instrument for international professional networking.[viii] Furthermore, for years, the proliferation of internet-connected devices has radically altered how audiences consume creative content,[ix] a trend that has been heightened by the shift to digital collaboration, creation, production, and promotion during the current COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing shut-downs of travel, border closings, and social distancing and lockdown measures.

Digital dance researcher Scott deLahunta, posits that “computer related technologies have not attained the level of integration within the field of dance as with the other art forms for the obvious reason that as a material the body in motion does not lend itself to digitization;”[x] so what happens when “the body in motion” has no option but to digitize? Drawing on the experiences of dance teachers, choreographers, and practitioners through interviews and publications, this article addresses the question arising when considering our ‘post-human’ reality: how does an embodied artistic practice, with its inherently physicalized creative process, transition into virtual online spaces? And what becomes our ‘new normal’ once we have the option of in-person practice again?

Posthumanism

This increase in (and ubiquity of) technology, theorists argue, exemplifies our becoming “posthuman.”[xi] Posthumanism signifies “a new way of understanding the human subject in relationship to the natural world”[xii] that rejects the hierarchy of humans over nature. It posits that humans exist within a wider ecology that blends species, technology, and the environments they occupy. It includes technology as a source for human reconfiguration and redefines human subjectivity through interaction with, in particular, technology. In other words, where technology is concerned, the digital is “embedded in the social lives and embodied practices of their users”[xiii] and contribute to our meaning-making. Further, the blended ecology that humans exist within is experienced through perceptual-sensory capacities of the organic system, which includes our engagement with technology.[xiv]

With regards dance practices, choreographer Carol Brown echoes this perspective when she states, “Our habitat is technological as much as geographical; we live in a digital infrastructure as much as a physical one.”[xv] Recognition of the wider, posthuman field of understanding, meaning-making, and affordance is therefore essential in digital dance. The experience of shifting dance practice to online formats was, for many in the field, one of necessity rather than choice—and furthermore one made without much notice. As such, practitioners and educators may not have had adequate time to reconcile this reality with their previous experience of live-only practice. Yet, such a distinction is important when transitioning to digital realms. As Luke Kahlich of Temple University, articulates

part of the issue for both educators and students was the abrupt transition from live to virtual. […] A block for dance educators/artists regarding technology has been and continues to be expectations that it will simply be the same except virtual. They are two different worlds, each with their strengths and challenges. Simply throwing a live experience onto the screen is unfair to all participants and perhaps even to the material itself.

As posthumanist Rosi Braidotti argues, “Art is […] posthuman by structure, as it carries us to the limits of what our embodied selves can do or endure.”[xvi] She emphasises embodiment and embeddedness as posthumanist principles.[xvii] When considering the re-framing of dance practice from live, in-person to digital, in-quarantine lockdown, a consideration of the element of embodiment, or our awareness of our lived perception of our bodies, becomes central.

The Challenge of Embodiment

As technology progresses to become more appealing to humans, it becomes “profoundly embodied, and conversely as profoundly disembodied, dispersed through the texture of the cyberworld.”[xviii] Within dance-tech practice on digital platforms—such as teaching or rehearsing over zoom rather than in person, Brown notes, “‘the ‘being in the body’ of embodiment is radially reconfigured.”[xix] Embodiment, or the ability to attune to our physicality and stay connected to that sense, is of utmost important in contemporary dance practices,[xx] and is frequently lamented as missing in digital practice. In such digital environs, we can “exist” without/outside of our bodies, and the immediate, felt sensation of the live body can become obscured—a (dis)embodiment and lack of connection to ourselves, and others, through this immediate felt sensation. Instructor of East African dances at the University of Auckland, Alfdaniels Mabingo, notes, “When you’re there in studio, you’re using all your senses; sight, touch, sound, smell. This deepens the connections. You don’t use all those senses on Zoom. It feels like each student is in their own world. The lack of embodied connection makes it difficult.”[xxi]

Juliet Chambers-Coe, of University of Surrey, remarks, “I took many strategies to ensure that the ‘virtual’ didn’t mean ‘not embodied.’ The transition to online spaces which removed physical proximity to others made one’s own proximity to self and awareness of one’s own embodied processes even more important.” Through this lens, then, and removed from the “external” objectifying gaze of a mirrored studio[xxii] or the pressure of other participants in the room, there may be potential for increased awareness of embodiment—provided ones’ practice recognises the affordances of the digital field, and does not simply seek to replicate such objectification or pressure through the screen. Options such as asynchronous learning, webcam-off options, or merely the intention towards practices emphasizing embodied awareness rather than replication or performance offer such shifts. Chambers-Coe adds that online classes “were invitations into our own bodies whilst allowing the senses to respond to others seen, heard and imagined on screens,” stating that she encouraged screens on, but with an emphasis on sharing environment rather than showcasing one’s movement performatively, leading to “images of windows, beds, vases, doll’s houses, feet, shoes, hallways, doors, gardens, sky” rather than merely the disciplined moving body. This allowed for a sharing of space, if not occupying the same spaces, with sound and other sensory input while exemplifying a reduced emphasis on visual engagement with other participants; as such it is one example of how technologies can facilitate connection (with others and with ourselves) despite their “disembodied” nature. As Whatley and Varney note, “Unless dancers are able to enter receptively to new temporal and aesthetic spaces, the inadequacies of the technologies prohibit further discovery and can mean breakdown and frustration.”[xxiii] However, it seems that practitioners and participants willing to “enter receptively” and embrace the challenges of encouraging embodiment in digital practice are optimistic about the possibility of a digitally-enhanced sense of embodiment. As Professional Teaching Fellow of Dance Movement Therapy at the University of Auckland, Jung-Hsu Jacquelyn Wan, comments, “I do think there’s a meeting point where we ‘transform and transcend’ the virtual space to a shared embodied space.”

Equity Concerns

As Mills argues, “Lockdown has posed immense challenges for us, as moving, social and embodied beings. […] The lockdown has, paradoxically, opened up new ways to experience dance, for dancers and spectators alike.”[xxiv] Such rare, life-changing events are seen by some as opportunities to create new futures,[xxv] while others note such events highlight and exacerbate existing inequalities.[xxvi] Considering this shift as a moment of potentiality for dance must necessitate recognition of these inequalities, and a vision for their amelioration in future iterations of dance practices. Some educators have expressed concern with these inequalities; Nalina Wait, from The Australian College of Physical Education in Sydney, remarks that the most central concern for her in shifting to digital methods was, “navigating the severe imbalance in terms of student resources. Consistent access to technology and space is easy for some but very challenging for many.” Wait’s perspective is supported by research addressing technological capital and access as a barrier for students,[xxvii] and which emphasises that accessibility is an intersectional issue, more greatly affecting minority and lower-income participants.[xxviii] If dance is to retain the benefits of online practice, we must also consider and address underlying inequities, including access, and increased effects of COVID-19 on certain communities.[xxix]

With these imbalances in mind, Doug Risner of Wayne State University notes, that he engages in “pedagogical activism,” or “working for social change in dance education.”[xxx] For him, one way to approach digital practice is through application of humanizing pedagogy[xxxi] in the digital environment. Freire [xxxii] defines humanizing pedagogy as an approach to education that “ceases to be an instrument by which teachers can manipulate students, but rather expresses the consciousness of the students themselves.” Dance leaders who engage with humanizing pedagogy aim for “mutual humanization” with participants, where dancers are in dialogue with dance leaders. Exemplifying this, Risner states, “What’s most important to me at this time is acknowledging and addressing the intense experiences and feelings of loss that both teachers and learners are navigating in not seeing each other in person and the ways in which human connection is significantly diminished.” He notes that humanizing digital practices can build relationships, connection, and empathy “to support deep engagement and heighten rigor.” Similarly, Li, Zhou, and Teo [xxxiii] note, “one of the strengths of the online community is its participatory nature.”

This is especially pertinent to dance, which requires physical and embodied participation alongside other, more typical means of digital engagement with community (like commenting or sharing content). It also has relevance for mental health concerns due to the loss of connection or community, with early research during the pandemic cautioning against “deterioration of mental health, even in those without pre-existing mental health” struggles.[xxxiv] Accordingly, dancers seem to have embraced digital practices during lockdown. Choreographer and professional dancer Andrea Lanzetti of upstate New York notes, “I felt more connected to the wider dance community. There isn’t much of a dance community where I live so [dancing online during lockdown] gave me a chance to connect to the broader community.” Likewise, Megan Mizanty of Wilson College comments, “There is also a sense of ‘being with’ when taking dance classes online that feels so needed right now.” And Mills[xxxv] notes that, “For myself, as well as for many others, dancing in self-isolation has created a vital community that has sustained us.” The reflections of these dancers appears to be in line with advice from Diamond and Willan [xxxvi] that those social distancing practice connection, physical activity, and routine as remedies to mental health threats.

Further, Risner argues, “Humanizing and immersive activities support students who are experiencing trauma as a result of racial injustice, stereotyping, and other forms of trauma and marginalization,” presenting a humanizing approach to digital practice as one option for a better (digital) future. On the other hand, however, he notes, “the online environment brings up a number of communication challenges not confronted in the traditional classroom,” and that “the online environment requires closer attention to the voice, tone, purpose, and scope of feedback” provided—an aspect which can be much more time-consuming for dance leaders.[xxxvii] This is especially concerning when research shows that women and BIPOC leaders are more heavily burdened with pastoral care[xxxviii] and judged more harshly by students/participants.[xxxix]

Further, the pandemic’s economic impact has struck the arts especially hard,[xl] and dance, as historically one of the less-funded art forms, has become particularly vulnerable. The pandemic has caused cuts to national and international touring, residencies, and more for the dance sector. As Heyang and Martin[xli] report a repercussion of COVID-19 is the inability to carry out international dance activities, though they recommend consideration of “how we might work together internationally, with less emphasis on economic or status imperatives” and more emphasis on collectivism. Again here, a shift to digital practices belies an optimistic future: it offers opportunities for collaboration and professional connection for artists regardless of stage of career or “success,” without the high cost of “corporeal mobility”[xlii] that has previously been the sole remit of larger companies and better-funded/higher profile artists.

The New Normal

As the world goes through second and third “waves” of coronavirus cases, lockdowns lift and return, and one question floats to the surface of our minds: what will be our “new normal?” It is perhaps too early to speculate how the rapid shift to digital dance practice may impact future in-person teaching, training, creating, and performing. However, one thing remains clear across the practitioners surveyed: there is a sense that this experience offers an opportunity change our practice, allowing us to retain the beneficial aspects of digital practice. Chambers-Coe comments “The ‘new normal,’ perhaps with hybrid in-person and remote methods might include a greater sense of attunement to one’s own senses of embodiment which extend to others in the spaces they share physically or otherwise.” Risner, too, seems optimistic, stating, “I want to emphasize both the opportunity and potential for highly positive outcomes made possible through meaningful instructor-learner relationships in online courses, especially generous feedback and rich dialogue.” Whatever is to come, let us all hope that this trying period of our human and artistic history leaves us with some lessons to build a better, more inclusive, future for dance.

Rebecca Weber (PhD, MFA, MA, RSME, RSDE, FHEA) investigates intersections between dance, science, and somatics from theoretical, practical, and artistic approaches. She is currently a Lecturer in Dance Studies at the University of Auckland. Weber holds a PhD in Dance Psychology from Coventry University, funded by the Leverhulme Trust. She is a registered somatic movement and somatic dance educator who has published widely, including in the anthology Dance, Somatics, and Spiritualities: Contemporary Sacred Narratives, which she co-edited. As director of Somanaut Dance, her work has been presented internationally and supported by Dance/USA, Dance/UP, World Dance Alliance Americas, Decoda, Mascher Space Co-operative, the Rebecca Skelton Fund, and others. In addition to being Director of Somanaut Dance and Co-Director of Project Trans(m)it, Weber is also an Associate Editor of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities, and Board Member of Carolina Dancer Wellness. www.somanautdance.com | www.projecttransmit.com

Further Reading

Ambrose, A. (2020). ‘Inequities During Covid-19.’ Pediatrics 146 (2) e20201501; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1501.

Anderson, Jon D. 2012. ‘Dance, Technology, and the Web Culture of Students.’ Journal of Dance Education 12 (1): 21–24.

Anker, V. (2008). Digital Dance: The Effects of Interaction between New Technologies and Dance Performance. Saarbrucken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

Anonymous. (2020). “Teaching East African Dance on Zoom, from a West Auckland Living Room.” News and Opinion, University of Auckland. Available at https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/news/2020/05/26/teaching-east-african-dance-from-west-auckland-living-room.html.

Anonymous. 2004. ‘Does the Increasing Use of Technology in Dance Detract from the Human Element?’ Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance 75 (8): 11–12.

Baker, Peter. 2020. “‘We Can’t Go Back to Normal’: How Will Coronavirus Change the World?” The Guardian, 31 March. Accessed 4 April 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/31/how-will-the-world-emerge-from-the-coronavirus-crisis.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, Duke University Press.

Barrios Solano, M. (2016) “Dance-Tech.” Accessed 20 Dec 2016. Available at: http://www.dance-tech.net/.

Blades, H. (2015). ‘Affective Traces in Virtual Spaces: Annotation and Emerging Dance Scores.’ Performance Research 20 (6): 26–34.

Bleeker, Maaike. (2016) Transmission in Motion: The Technologizing of Dance. London: Routledge.

Bolter, J. (2016) “Posthumanism,” in The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy, Edited by Bruhn Jensen, K. and Craig, R. pp. 1-8. Wiley & Sons.

Bonin-Rodriguez, Paul, & Vakharia, Natalie. 2020. ‘Arts Entrepreneurship Internationally and in the Age of COVID-19.’ Artivate, 9(1), 3-7. doi:10.34053/artivate.9.1.0003.

Braidotti, R. (2013) The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

Brown, C. (2006) “Learning to Dance with Angelfish: Choreographic Encounters between Virtuality and Reality” in Performance and Technology, edited by: Broadhurst, S. and Machon J. pp 85-99. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

deLahunta, S. 2002. “Periodic Convergences: Dance and Computers.” In Dance and Technology: Moving Towards Media Productions, edited by S. Dinkla and M. Leeker. Berlin: Alexander Verlag.

Diamond, R., and Willan, J. (2020). ‘Coronavirus disease 2019: achieving good mental health during social isolation.’ The British Journal of Psychiatry: the journal of mental science vol. 217,2: 408-409. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.91.

Ehrenberg, S. (2015). A Kinesthetic Mode of Attention in Contemporary Dance Practice. Dance Research Journal, 47(2), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767715000212.

Ehrenberg, S. (2010). Reflections on reflections: mirror use in a university dance training environment. Theatre, Dance & Performance Training, 1(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2010.505001.

Freire, P. (1970) The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Harss, Mariana. 2020. ‘Dancing on their own during the Coronavirus crisis,’ The New Yorker. Accessed 9 Aug 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/dancing-on-their-own-during-the-coronavirus-crisis.

Heyang, T. and Martin, R. (2020). ‘A reimagined world: international tertiary dance education in light of COVID-19,’ Research in Dance Education. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1080/14647893.2020.1780206

Kammerbauer, M., and Wamsler, C. (2017). ‘Social Inequality and Marginalization in Post-Disaster Recovery: Challenging the Consensus?’ International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 24: 411–418.

Karreman, L. (2013) ‘The Dance without the Dancer: Writing Dance in Digital Scores.’ Performance Research 18 (5): 120–128.

Knox, E. (2016) “’Face Robots’ Onscreen: Comfortable and Alive”. In Cultural Robotics, Edited by: Koh, J., Dunstan, B., Silvera-Tawil, D., and Velonaki, M. p. 133-142. Springer.

Lazos, S. (2012) “Are Student Teaching Evaluations Holding Back Women and Minorities?: The Perils of “Doing” Gender and Race in the Classroom” in Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia, Edited by Gutiérrez y Muhs, G., Flores Neimann, Y., González, C., Harris, A. Utah State University Press, 164-185.

Lepczyk, B. (2009). “Technology Facilitates Teaching and Learning in Creative Dance.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 80 (6): 4–8.

Li, Z., Zhou, M., and Teo, T. (2018). ‘Mobile Technology in Dance Education: A Case Study of Three Canadian High School Dance Programs.’ Research in Dance Education 19 (2): 183–196.

Mair, S. (2020). ‘How Will Coronavirus Change the World?’ BBC Future, 31 March. Accessed 2 April 2020. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200331-covid-19-how-will-the-coronavirus-change-the-world.

Mills, D. (2020). ‘Lockdown dancing is both a solo conversation and a mass grieving,’ Psyche 10 Aug 2020. Available at https://psyche.co/ideas/lockdown-dancing-is-both-a-solo-conversation-and-a-mass-grieving.

Nayar, P. (2014). Posthumanism. Cambridge: Polity.

Norman, S. J. (2006). ‘Generic versus Idiosyncratic Expression in Live Performance Using Digital Tools.’ Performance Research 11 (4): 23–29.

Paton, K. 2020. ‘While the creative sector hurts, the power of making carries us through.’ The Spinoff. 18 Apr 2020. Accessed 5 Aug 2020. https://thespinoff.co.nz/art/18-04-2020/while-the-creative-sector-hurts-the-power-of-making-carries-us-through/.

Parrish, M. 2007. “Technology in dance education”. In International handbook for research in arts education, Edited by: Bresler, L. 1381–97. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Pearson, R. 2019 “A feminist analysis of neoliberalism and austerity policies in the UK: Women are increasingly treated as an expandable and costless resource that can absorb all the extra work that results from cuts to the resources that sustain life,” Surroundings 71; 28-39.

Risner, D. and Anderson, J. (2008). ‘Digital Dance Literacy: An Integrated Dance Technology Curriculum Pilot Project 1.’ Research in Dance Education 9 (2): 113–128.

Risner, D. (2019): Activities for Humanizing Dance Pedagogy: Immersive Learning in Practice, Journal of Dance Education, DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2019.1678753.

Risner, D. (2014) ‘Hold on to This!: Strategies for Teacher Feedback in Online Dance Courses,’ Journal of Dance Education, 14 (2): 52-58, DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2014.865190.

Rodd, P. and Sanders, K. 2018. ‘The Imperative of Critical Pedagogy in Times of Cultural Austerity: A Case Study of the Capacity to Reimagine Education as A Tool for Emancipation.’ New Zealand Sociology 33 (3): 33.

Roy, S. 2001. ‘Technological Process.’ Dance Theatre Journal 17 (4): 32–35.

Tomczak, K. 2011. ‘Using Interactive Media in Dance Education.’ Journal of Dance Education 11 (4): 137–139.

Schiller, G. (2002). ‘Interactivity as Choreographic Phenomenon.’ In Dance and Technology: Moving towards Media Productions, edited by Dinkla, Soke and Leeker, Martina. 164–195. Berlin: Alexander Verlag.

Schiphorst, T. 1992. ‘LifeForms: Design Tools for Choreography.’ In Dance and Technology 1: Moving toward the Future, edited by A. W. Smith, 46–52. Fullhouse Publishing.

Sicchio, K. 2014. ‘Hacking Choreography: Dance and Live Coding.’ Computer Music Journal 38 (1):31–39.

Skybetter, S. (2014). ‘How Will We Dance? Where is the Art Form Headed in 2015 and beyond.’ Dance Magazine 88 (12): 83–85.

Storme, T., Faulconbridge, J., Beaverstock, J., Derudder, B., and Witlox, F. (2017). ‘Mobility and Professional Networks in Academia: An Exploration of the Obligations of Presence.’ Mobilities 12 (3): 405–424.

Tomczak, K. 2011. “Using Interactive Media in Dance Education.” Journal of Dance Education 11 (4): 137–139.

Valverde, I., and Cochrane, T. (2014). ‘Innovative Dance-Technology Educational Practices within Senses Places.’ Procedia Technology 13 (122): 129.

Wadhwa, R. (2016). ‘New Phase of Internationalization of Higher Education and Institutional Change.’ Higher Education for the Future 3 (2): 227–246.

Weber, R., Mizanty, M., and Allen, L. (2017). ‘Project Trans(m)it: creating dance collaboratively via technology – a best practices overview.’ Research in Dance Education 18 (2), 116-134. 10.1080/14647893.2017.1354840

Whatley, S., and Varney, R. (2009). ‘Born Digital; Dance in the Digital Age.’ International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 5 (1): 51–63.

[i] Harss, “Dancing on their own during the Coronavirus crisis.”

[ii] deLahunta, “Periodic Convergences: Dance and Computers.”

[iii] “Born Digital; Dance in the Digital Age,” 52.

[iv] Risner and Anderson, “Digital Dance Literacy: An Integrated Dance Technology Curriculum Pilot Project 1”; Tomczak, “Using Interactive Media in Dance Education”; Lepczyk, “Technology Facilitates Teaching and Learning in Creative Dance”; Anonymous, “Does the Increasing Use of Technology in Dance Detract from the Human Element?”; Anderson, “Dance, Technology, and the Web Culture of Students.”

[v] Anker, Digital Dance: The Effects of Interaction between New Technologies and Dance Performance; Norman, “Generic Versus Idiosyncratic Expression in Live Performance Using Digital Tools”; Roy, “Technological Process”; Schiller, “‘Interactivity as Choreographic Phenomenon’”; Schiphorst, “LifeForms: Design Tools for Choreography”; Siccio, “Hacking Choreography: Dance and Live Coding”; Valverde and Cochrane, “Innovative Dance-Technology Educational Practices within Senses Places”; Weber, Mizanty, and Allen, “Project Trans(m)It: Creating Dance Collaboratively via Technology–a Best Practices Overview.”

[vi] Blades, “Affective Traces in Virtual Spaces: Annotation and Emerging Dance Scores.” ”; Karreman, “The Dance without the Dancer: Writing Dance in Digital Scores”; Whatley and Varney, “Born Digital; Dance in the Digital Age.”

[vii] Bleeker, Transmission in Motion: The Technologizing of Dance.

[viii] Barrios Solano, “Dance-Tech.”

[ix] Skybetter, “How Will We Dance? Where Is the Art Form Headed in 2015 and Beyond,” 83.

[x] deLahunta, “Periodic Convergences: Dance and Computers,” 66.

[xi] Nayer, Posthumanism; Braidotti, The Posthuman; Barad, Meeting the universe halfway.

[xii] Bolter , “Posthumanism,” 1.

[xiii] Bolter , “Posthumanism,” 5-6.

[xiv] Nayar, Posthumanism, 9.

[xv] Brown, “Learning to Dance with Angelfish,” 95.

[xvi] Braidotti, The Posthuman, 107.

[xvii] Braidotti, The Posthuman, 51.

[xviii] Knox ’Face Robots’ Onscreen, 138.

[xix] Brown, “Learning to Dance with Angelfish,” 85.

[xx] Ehrenberg, “A Kinesthetic Mode of Attention in Contemporary Dance Practice.”

[xxi] Anonymous, “Teaching East African Dance on Zoom,” n.p.

[xxii] Ehrenberg, “Reflections on Reflections: Mirror Use in a University Dance Training Environment.”

[xxiii] Whatley and Varney, “Born Digital; Dance in the Digital Age,” 54.

[xxiv] Mills, “Lockdown dancing is both a solo conversation and a mass grieving,” n.p.

[xxv] Baker, “‘We Can’t Go Back to Normal’: How Will Coronavirus Change the World?”; Mair “‘How Will Coronavirus Change the World?’”; Rodd and Sanders “The Imperative of Critical Pedagogy in Times of Cultural Austerity.”

[xxvi] Kammerbauer & Wamsler , “Social Inequality and Marginalization in Post-Disaster Recovery”; Wadhwa “New Phase of Internationalization of Higher Education and Institutional Change.”

[xxvii] Risner and Anderson, “Digital Dance Literacy: An Integrated Dance Technology Curriculum Pilot Project 1”; Parrish, “Technology in dance education.”

[xxviii] Parrish, “Technology in dance education.”

[xxix] Ambrose “Inequities During Covid-19.”

[xxx] Risner, “Activities for Humanizing Dance Pedagogy”, 1.

[xxxi] Friere, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

[xxxii] Ibid., 51.

[xxxiii] Li, Zhou, and Teo, “‘Mobile Technology in Dance Education,” 193.

[xxxiv] Diamond and Willan “Coronavirus disease 2019”, 408.

[xxxv] Mills, “Lockdown dancing is both a solo conversation and a mass grieving,” n.p.

[xxxvi] Diamond and Willan “Coronavirus disease 2019.”

[xxxvii] Risner “Hold onto This!”, 52.

[xxxviii] Pearson, “A feminist analysis of neoliberalism and austerity policies in the UK.”

[xxxix] Lazos “Are Student Teaching Evaluations Holding Back Women and Minorities?.”

[xl] Bonin-Rodriguez & Vakharia, “Arts Entrepreneurship Internationally and in the Age of COVID-19;” Paton, “While the creative sector hurts, the power of making carries us through.”

[xli] Heyang and Martin, “A reimagined world,” 6.

[xlii] Storme et al, “Mobility and Professional Networks in Academia”; Heyang and Martin, “A reimagined world.”

Pingback: Digital Tech’s Impact on Our Favorite Physical Activities