by Naomi Alisa Calnitsky

“It is in no way extraordinary that the Valley was unable to understand Cesar Chavez. He belongs to that inarticulate subculture of farm workers upon whom the Valley depends but whose existence does not impinge heavily on the Valley consciousness. Their work is one of side roads and labor camps, of anonymous toil under a blistering sun. The very existence of farm workers is a conundrum. Because they have never been effectively organized, they have never been included under legislation that safeguards the rights of industrial workers; because they are excluded from the machinery of collective bargaining, they have never been able to organize effectively.”

– John Gregory Dunne, Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike

The United Farm Workers of America, a movement with origins in the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) and Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), is commonly remembered as the organization formed and led by César Chávez. Yet, the dynamic interactions between Chávez and other critical figures in its history, such as Fred Ross, Dolores Huerta, and Chávez’s brother Richard, the designer of the UFW flag, would prove critical to its impact and success. While Chávez would inspire other farm labor leaders outside of California, differences of opinion, especially with respect to the question of organizing undocumented workers in agriculture, allowed some successes to occur outside the boundaries of the UFW movement. This was especially the case in states like Arizona, where successful strike activities took place in the late 1970s in defense of the rights of undocumented workers.

Differences of opinion concerning whether or not undocumented workers had the right to be militant provoked a number of internal fissures within the fabric of national movement. Leaders like Cipriano Ferrel would go on to foment radical and protective organizing in the Pacific Northwest in favor of vulnerable workers vis-à-vis Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) raids, yet his activism would form its own unique trajectory. Ferrel had formed links with Chavez early on, first gaining organizing experience through his involvement with the UFW.[1]

An expansion of the H-2A guest work scheme has increasingly tied harvest workers in the United States to a single employer.

After a golden age that spanned the 1960s through the mid-80s, the movement Chávez built would weaken and cease to persist as a unifying political force in the twenty-first century. However, notwithstanding assessments of the UFW as a movement that has entirely lost significance, the United Farm Workers still perform bargaining activities, making agreements recently with large-scale vegetable producers in California and dairy farms in Oregon while securing victories in the strawberry, rose, wine, and mushroom industries.[2] Despite these gains, an expansion of the H-2A guest work scheme has increasingly tied harvest workers in the United States to a single employer, depriving them of many of the rights they might receive as nationals.[3]

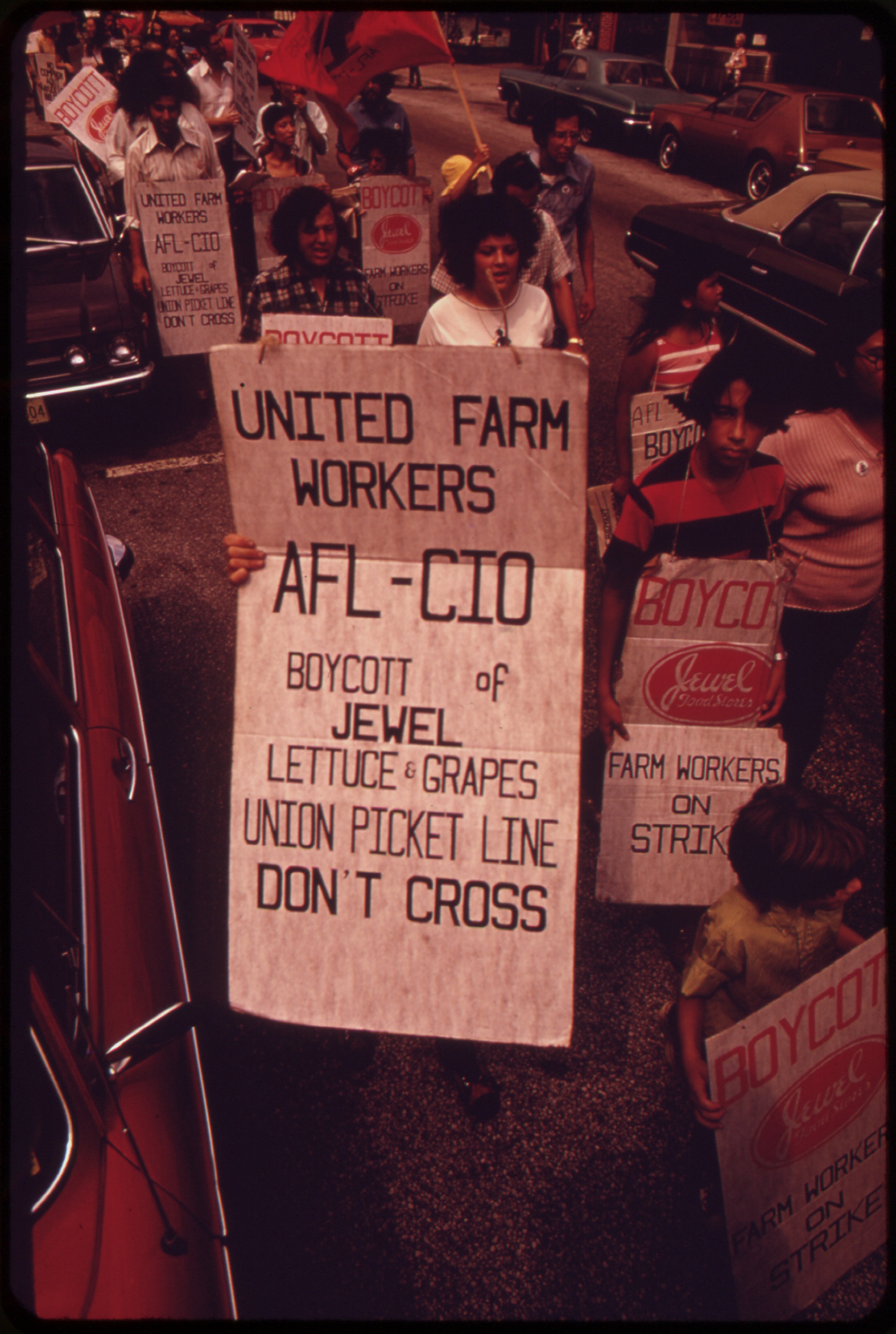

Photo by Paul Sequeira. Courtesy Wikimedia.

The Grassroots UFW

One successful tactic the UFW borrowed from the civil rights movement, the boycott, raised awareness of the mistreatment of Latino farmworkers. Their slogan “¡Si se puede!” (Yes We Can), a hallmark of the UFW cause, had powerful reverberations in its time. Through its “anti-grower message,” early grassroots media generated from the farm worker movement in 1960s California—like “The Voice of the Farm Worker,” El Macriado—implicated a “rowdy youth who does not give due respect to his ‘betters.’”[4] In addition to radical media, other tactics like marches, boycott campaigns, and public fasts helped facilitate in the public sphere recognition for the farm worker class and the struggles they faced.

Beyond politics, the UFW was built upon spiritual foundations. The cursillista tradition, a religious trend that migrated from Spain to the United States in 1950, offered a version of Catholicism championed by many of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent in the United States who could not find a comfortable place within American church life. The cursillo movement blended well with the farmworker movement; Latino folk songs merged with Spanish liturgy and the cursillo song “De Colores” would become the UFW’s anthem. Ballads like “De Colores” were often sung at UFW gatherings, marches, and rallies. The concept of ultreya (forward) also inspired a rejection of half-measures that was a basis for the movement’s capacity to unite its followers. “De Colores” ends with the phrase “In colors, in colors / Is the rainbow that we see shining.” This message tied the UFW cause into a more singular vision rooted in the ideals of equality and social justice, and the song was often accompanied by the cry “¡Si se puede!”—a call for political optimism.

El Plan De Delano was a manifesto drawn up in 1966 to address the iniquities in farm work, and it was read at every stop on the pilgrimage from Delano to Sacramento. Three years later, El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan, drafted at the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in Denver, reflected a broad range of “social, political, and cultural concerns,” demanding “improved housing, education, employment, self-determination, and self-defense.”[5] According to Michael Pina, “more striking than the particular demands this plan issue[d] [was] the ideological base from which they [were] launched;”[6] it wove in a legend of Aztlán—the mythical home of the Aztecs—into the fabric of a manifesto that called for its “geographical and spiritual resurrection” in a context of Chicano nationalism.[7]

An Inspired Leadership

Dolores Huerta, instrumental as an organizer and speaker for the cause of migrant farmworkers, is often remembered as the adelita, or female militant, of the farmworkers’ struggle. Huerta presented a range of public faces from “emotionality” and emphasis on family to “collaborative egalitarianism” and “courageous optimism.” [8] As Vice President of the UFW and a founding member of the NFWA, Huerta was instrumental in helping to carve out improved rights and conditions for workers in California and elsewhere. The legacy of her work still informs causes linked to gender equality and the women’s movement.

A sense of optimism had always pervaded the vanguard of the UFW leadership, and despite the eventuality of their elevated political and public statuses, many of its leaders had origins in the working class. Born into the farmworker class, as Frank Bardacke describes in his organizational biography, Trampling out the Vintage, Chávez came to view farm labor in exchange for a wage as an affliction and inescapable system of servitude. As a critic of the Bracero Program, he pointed out the problems associated with contracting workers directly from Mexico, most significantly that they were replacing opportunities for local able-bodied labor to find work. Similar criticisms were voiced in Manitoba, Canada in the 1970s, when it was thought they might take jobs away from First Nations workers.

Eliseo Medina first read El Macriado in 1965 and recalled thinking: “all of a sudden, it was like Mexicans could do something and they could win.”[9] Born in Zacatecas to a bracero father, Medina ultimately became a key organizer who led the Chicago Grape Boycott for the UFW. As Miriam Pawell notes, his organizational career was shaped by practical and informal approaches, and his lifelong activism has persisted into the twenty-first century. In 2014, he fasted for progressive immigration reform.

Churchmen and labor leaders also figured prominently in the social web that constituted the farmworker movement.

Churchmen and labor leaders also figured prominently in the social web that constituted the farmworker movement. Interrelationships between California bishops and the UFW were significant, just as Mexican migrant workers in Canada have relied upon the support of ministers who have conduct critical outreach activities in rural towns that employ migrant workers without any profit motive or aims for economic gain. Labor leaders played an equally important role: George Meany of the AFL-CIO, initially skeptical of the idea of organizing the farmworker class, eventually committed himself to the UFW cause. Numerous church leaders, inspired by social justice ideals, including Priest Monsignor Higgins, would soon become critical endorsers of La Causa, but perhaps more importantly the events that saw an outpouring of Latino civic engagement in 1960s California were propped up by religious foundation.

Speaking in Winnipeg in 1971, Jessica Govea, an assistant to Chávez, recounted how one Manuel Rivara was injured on the picket line by a farmer; Rivara was later “told by a California judge that he was ‘lucky’ not to be prosecuted himself for obstructing a public roadway.”[10] Similarly in Canada, a Canadian Labour Congress report documented the case of one Teresa from Mexico who, while working on an Ontario apple orchard, “fell off a tractor, which then ran over her legs.” After undergoing surgery twice she faced reprimands from a Mexican Consular official who “blamed her for being clumsy” and “demanded…she sign a document confirming his version of the accident.”[11]

Farm workers still face intermittent violence, especially when working with uncertain statuses. Rural labor conflicts, shaped in part by differences of nationality or class, have come to intersect in powerful ways with diverse agribusiness climates.[12] Recent changes to agricultural guest work visas have offered regressive “solutions” to the important and interrelated question of agricultural work, legality, and freedom of mobility within the labor market.[13]

Indeed, while the impact of the United Farm Workers is perhaps not as strongly felt in the twenty-first century as it might be, its pedagogical relevance makes it perhaps more significant now than ever. In seeking to restore dignity and equality to the downtrodden worker, collective resistance and power in numbers have helped win contracts and renegotiate terms in a troubled sector whose economic success has forever rested upon a perpetual race to the bottom.

Naomi Calnitsky is an independent scholar, researcher, and oral historian, with a focus on histories of migration and colonialism in North America and the Western Pacific. Her forthcoming book, Seasonal Lives: Twenty-First Century Approaches (University of Nevada Press) comparatively explores the stories of farm worker migrations in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States from the mid-nineteenth century through to the present day.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Notes

[1] Mario Sifentez, “The Genesis of the Willamette Valley Immigration Project,” Chapter Three in Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Unvirsity Press, 2016). 59.

[2] See “Our Vision,” Available at ufw.org. Accessed 1 July 2015.

[3] Dan Charles, “Guest Workers Legal, Yet Not Quite Free, Pick Florida’s Oranges,” NPR January 28, 2016. Available at http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/01/29/464758284/activists-demand-a-bill-of-rights-for-california-farm-workers. One of the best sources on the shifting harvest labor climate is Philip Martin’s Rural Migration News, https://migration.ucdavis.edu/rmn/.

[4] Origins of El Macriado by Doug Adair and Bill Esher Rampujan 2009. UC San Diego Farmworker Movement Documentation Project. https://libraries.ucsd.edu/farmworkermovement/ufwarchives/elmalcriado/billEsher.pdf

[5] Michael Pina, “The Archaic, Historical, and Mythicized Dimensions of Aztlán,” in Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland (Revised and Expanded Edition), Edited by Rudolfo Anaya, Francisco A. Lomelí and Enrique R. Lamadrid (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017; Orig. Edition El Norte Publications/Academia, 1989), 68.

[6] Ibid., 69.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See Stacey Sowards, “Rhetorical Agency as Haciendo Caras and Differential Consciousness Through Lens of Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Class,” Communication Theory 20 (2010): 223-47.

[9] Miriam Pawell, The Union of their Dreams: Power, Hope and Struggle in César Chávez’s Farm Worker Movement (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009), 48-9.

[10] “‘Hope Pledged’ to NFU Dispute,” Winnipeg Free Press, Thursday, Dec. 9, 1971.

[11] Karl Flecker, Canadian Labour Congress, Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP): Model Program or Mistake? (Ottawa: Canadian Labour Congress, 2011) 1-2.

[12] This was the case in Greece in 2016 with undocumented Bangladeshi strawberry harvest workers. See Helena Smith, “Greece’s Migrant Fruit Pickers,” The Guardian, Sept. 1, 2014.

[13] See for example, http://www.thefencepost.com/news/goodlatte-defends-ag-guestworker-bill-conyers-ufw-oppose-it/.

References

Anaya, Rudolfo, Francisco A. Lomelí and Enrique R. Lamadrid, eds. Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland (Revised and Expanded Edition). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017.

Bardacke, Frank. Trampling out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers London and New York: Verso, 2011.

Charles, Dan. “Guest Workers Legal, Yet Not Quite Free, Pick Florida’s Oranges,” NPR January 28, 2016.

Dunne, John Gregory. Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967.

Pawell, Miriam. The Union of their Dreams: Power, Hope and Struggle in César Chávez’s Farm Worker Movement. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Sifuentez, Mario Jimenez. Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Unvirsity Press, 2016.

Smith, Helena. “Greece’s Migrant Fruit Pickers,” The Guardian, Sept. 1, 2014.

Sowards, Stacey. “Rhetorical Agency as Haciendo Caras and Differential Consciousness Through Lens of Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Class: An Examination of Dolores Huerta’s Rhetoric,” Communication Theory 20 (2010): 223-247.

0 comments on “Lessons from La Causa: Leadership, Spirituality and Geographies of Injustice in an Era of Civil Rights”