Also this week: Lewis Eliot’s analysis of the impact of the Haitian Revolution on British Romantic poetry reveals wavering public support of egalitarian abolitionism, while Evan Turiano’s analysis of the historiography of self-emancipation reveals the importance of historians’ approach to enslaved people.

by Nathan Wuertenberg

As Eric Morgenson pointed out in his essay opening our special issue on revolutions for the month of July, celebrations of US independence have often served as a poignant reminder of the inherent incompleteness of the founders’ promises of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration. For some, like Frederick Douglass, the jubilant cries of “freedom” that rang out from every bully pulpit on the Fourth harmonized uneasily with the reality of millions bound in chains. For others, like the Puerto Ricans that found themselves under US rule in the wake of the Spanish-American War, July Fourth was a harsh reminder that their own dreams of independence had been stymied by the ambitions of a foreign power. For the large majority of white Americans, on the other hand, the sacrosanctity of Independence Day has remained largely unquestioned. Around the United States, white liberals and conservatives alike gather together every year to share in the fleeting joys of grilled food, fireworks, and the collective decision to ignore that one uncle who thinks 9/11 was an inside job. It is, for many of its celebrants, the most American of holidays: a perfect opportunity to more fully appreciate the perceived blessings of living in the nation that won the Cold War, invented baseball, and landed a man on the moon.

In the past few years, however, a growing number of essays from white liberals have appeared online and in print describing the Fourth in terms not of celebration, but of regret. Indeed, questioning the necessity of American independence is rapidly becoming its own sort of yearly tradition for press outlets like Vox and The New Yorker. Had the United States remained thirteen disparate colonies, the argument goes, Americans would not be faced now with the evils of racism, sexism, homophobia, and free market healthcare. Instead, in the memorable words of the essay in The New Yorker, “we could have been Canada” (a land evidently devoid of the dark forces that plague our own). After all, the British Empire abolished slavery in 1833, a full thirty-two years before the United States, and had expanded its American holdings to our north through a more “orderly development of the interior” that was “less violent, and less inclined to celebrate the desperado over the peaceful peasant.” US independence was thus, for the authors of such essays, a resounding mistake, the consequences of which were so overwhelmingly destructive as to nullify any perceived benefits.

American success and the expansion that fueled it were rooted in acts of violence like the invasion against the Haudenosaunee, something that our founders not only perceived but encouraged.

The American War for Independence is undeniably central to the history of native genocide and slavery as the genesis of US imperialism. Conflict with British-allied native communities convinced rebel leaders to pour an increasing amount of resources into borderlands campaigns over the course of the war, in the process hastening the creation of bureaucratic state apparatuses in the West designed specifically to effect the destruction of native peoples. Perhaps most notably, delegates to the Continental Congress ordered an invasion of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) lands in western New York in the summer of 1779, diverting precious men and resources away from the eastern campaigns under Commander-in-Chief George Washington in order to retaliate against particularly effective raids by British-allied Senecas. The campaign opened, conveniently enough, with a celebration of the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The most notable toast? “Civilization or death to all savages,” a presentiment Continental troops did their utmost to fulfill over the course of the invasion. Their commander, General John Sullivan, was under strict orders from General Washington to bring about the “total destruction and devastation of [the Haudenosaunee’s] settlements by “ruin[ing] their crops now in the ground and prevent[ing] their planting more.” It was, in essence, a total war, one intended to erase any evidence of native presence from the very earth itself with the cleansing power of fire. Thousands of indigenous refugees were forced to flee in the face of such attacks to the British fort at Niagara in search of food and shelter. Meanwhile Congressional leaders reveled in their victory, certain that their indigenous opponents had been reduced to nothing more than, in the words of one delegate, “Flees.” Claiming the status of conquerors, they demanded punitive land cessions from the Haudenosaunee in return for peace, cessions that opened the way to territories even further west and laid the foundation for the creation of transportation and trade infrastructures between the Atlantic Ocean and Great Lakes like the Erie Canal that ensured the United States’ future success and continued expansion. That success and the expansion that fueled it were rooted in acts of violence like the invasion against the Haudenosaunee, something that our founders not only perceived but encouraged. Indeed, they bet their nation on it.

The Sullivan Expedition was neither the first nor the last such campaign during the war, and such conflicts convinced many white Americans that native peoples had no place in the nation being built at their expense. This conviction fed into a growing conception of the United States as an exclusively white nation, one where opportunities would abound, but only for those that fit socially accepted and politically enforced definitions of belonging. This conception was likewise fed by the endemic presence of slavery, an institution that was central not only to the newly founded nation but to the war that achieved its independence. Indeed, the perceived threat to the institution posed by Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775 offering freedom to any slave of rebel masters that escaped to serve in the British military motivated many southern colonists to support independence. As Evan Turiano points out in his essay for our “revolutions” issue, the centrality of British military emancipation to the course of the war has been a topic of much debate among scholars over the last seventy-odd years. Meanwhile, for popular audiences, the topic is rarely one for conversation at all, an oddity at best and an opportunity for a few mental gymnastics during a Mel Gibson movie at worst. Yet, for most (if not all) rebel slaveholders, the defense of slavery against emancipatory overtures was the very reason their new nation was being formed. It is little surprise, then, that when independence was won, American slaveholders refused to participate in any political system that did not guarantee protections for the institution that defined every aspect of their lives. When some at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 suggested that the new federal government should have the power to regulate the slave trade, for example, John Rutledge of South Carolina declared that the Southern states would “not be parties to this union” and threatened to leave, a tactic repeated by other slaveholding delegates throughout the Convention and ultimately one that worked. The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention and was sent to the states for ratification contained numerous clauses protecting the institution of slavery and ensconcing the power of slaveholders. The Southern states would not have accepted the Constitution if it had been otherwise, and the United States would not have remained united without them. So, the US was not just a collection of states, some slave states and some free. It was a nation that existed specifically because it protected slavery. It was a slave nation.

The American War for Independence thus ensured the creation of a nation whose success was built on a foundation of slavery and native genocide. But, those acts were not formed wholesale from the fabric of rebellion. The motivations of Continental soldiers calling for “death to all savages” and Southerners declaring independence to protect their ownership of slaves were both rooted in a century and a half of racial beliefs that only became further entrenched as time passed. To suggest that, with the stroke of a pen Britain might have been able to stop its colonists from continuing to monetize those beliefs is not only disingenuous, it ignores the multiple examples in which Britain attempted to do just that and ultimately was forced to acquiesce to the wishes of its colonial subordinates. The Royal Proclamation Line of 1763, for example, limited colonial expansion to the Appalachian Mountains in an effort to curb the violence of encounters between colonists and native communities. Instead, British troops in the borderlands spent the large majority of their time protecting the countless colonists that crossed the Proclamation Line despite their express orders and became just as entangled in the cycles of violence as the colonists that overwhelmingly chose to ignore the dictates of their king. Had the thirteen colonies remained in the Empire rather than rebelling, they most likely would have continued to disregard any imperial mandate that inconvenienced them. And, any such mandate that they perceived as an immediate threat to their most deeply entrenched belief systems (not to mention their financial success) could have provoked the very same murmurs of rebellion heard in the 1770s. Rather than ending slavery thirty-two years early, then, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 could very well have pushed American colonists to make the declaration of independence they had chosen to forgo fifty-seven years before.

Arguably the main impetus behind British abolition arose after the loss of the American colonies had allowed other European empires to supplant Britain in the slave trade and plantation economies, which lessened its profit motives for resisting abolition considerably.

Even the assumption that Britain would have still abolished slavery without American independence may be flawed. Some historians have argued, in fact, that the main impetus behind British abolition arose after the loss of the American colonies had allowed other European empires to supplant Britain in the slave trade and plantation economies, which lessened its profit motives for resisting abolition considerably and provided incentives for abolishing the slave trade in order to weaken imperial rivals. Still, even if Britain had still supported abolition and its colonies had agreed to submit peacefully to British abolitionism, American colonists would have been choosing to remain in an empire built on similar acts of exploitation and violence. During the American colonial period, British officials explicitly advocated for such acts, as in Commander-General Sir Jeffrey Amherst’s ruminations on the possible use of smallpox blankets against native peoples. They continued to do so long after. In the mid-nineteenth century, they openly encouraged opium addiction in China in order to profit from poppy production in recently gained territories in India, destroying millions of lives in the process. By systematizing the Indian caste system and applying it to the labor hierarchy of poppy cultivation, British officials were able to maximize their profits from the opium trade. They were so successful in this particular endeavor that they were ultimately able to finance their administration of India almost entirely through their trade in opium with China, a trade they forced China to accept through the First and Second Opium Wars. Such activities were the rule, not the exception, a product of the daily and systemic violence of British imperialism.

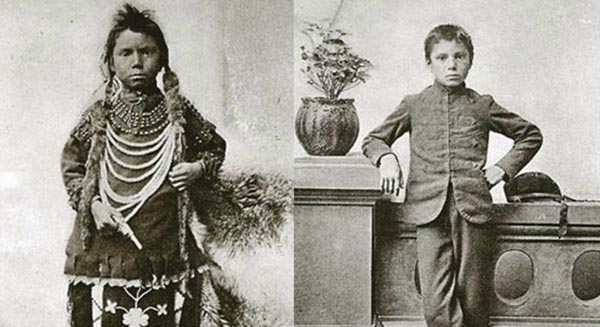

Even in Canada, the country the US “could have been,” violence was integral to westward expansion. The precursor to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (the North-West Mounted Police), for example, was formed expressly for the purpose of curtailing violence between settlers and indigenous groups after a band of American, Canadian, and Métis hunters and traders in what became Saskatchewan murdered almost two dozen Assiniboines in the Cypress Hills Massacre of 1873. Such acts were not isolated incidents, they were products of a larger system that favored the destruction of native peoples by whatever means necessary. When physical violence was not enough, authorities resorted to cultural violence, forcing native children to leave home for the notoriously abusive environments of boarding schools. As with boarding schools for native children in the United States like the Carlisle School, native children in Canadian boarding schools were refused contact with their families, forced to cut their hair, and beaten for speaking their natal languages. “Settlement” is not a peaceful process; it is an act of conquest, an invasion of foreign soil. The idea that Canada was created by “peaceful” means is as farcical as the idea that the United States was. Wishing independence away would not change that fact; it would only change the particularity of the violent acts committed. We would still be a product of imperialism — an inherently violent process. We would just have different sins to atone for. Just ask the native protestors that occupied Parliament Hill during the Canada 150 celebrations.

But, ultimately, I would argue that wishing away US independence isn’t so much about a desire to prevent historical sins so much as it is about a desire to ignore them. The milk has been spilled. Wishing it hadn’t been doesn’t clean up the mess, it just makes the ones who spilled it feel better because they’ve offered an empty apology to the ones they spilled it on. Rather than wishing independence away, we should instead, as Eric Morgenson recommended, use the Fourth of July as an opportunity to search for concrete ways in which we as the heirs to the violence of white American imperialism can ameliorate the suffering of those it has impacted most. We should also, however, continue this search every other day of the year as well. The violence of imperialism was a daily occurrence. Our support for reparations for that violence should be as well.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Pingback: ‘Domestic Insurrections Amongst Us’: A Critical Historiography of Slave Flight in the American Revolution – The Activist History Review

Pingback: Exultations, Agonies, and Love: The Romantics and the Haitian Revolution – The Activist History Review

This is an interesting start, but I don’t see how your post goes beyond an angrier version of the same empty apology, which directs blame for the American past at liberals who are attempting to start a conversation. You suggest that we should search for “concrete ways” to redress grievances. What specific policies would you support, and why didn’t you include them in the post?

Second, I think I take issue with the idea that we are, “heirs to the violence of white American imperialism.” Are all white Americans culpable in this way? Should a family who immigrated do the Untied States in the 1920s be implicated in the crimes of the colonial American past? If the answer is, “yes, because they are white and benefit from it,” doesn’t that say more about the era in which they exist than the colonial past?

Are modern Germans heirs to the violence of the Nazi Regime? Are residents of Spain heirs to the violence of the Reconquista? As someone who is a quarter Italian, am I an heir to the violence of the Roman Empire? Should I attempt to find individuals of Gallic and Parthian ancestry to pay reparations to? Or, on the flip side, should I seek reparations from individuals of Vandal, Gothic, and Hunnic ancestry? Does the decision-making processes of an individual’s biological ancestors make the descendant culpable and responsible for those actions?

I think there are more pressing and motivating reasons to take part in making the world a better place than assigning guilt based on ancestry and ethnic makeup. I am certainly a party to the violence currently raging in the middle-east, as I took part in a political system which elected the leaders responsible for that violence. As a human being, I should support equal opportunity and equal rights for all humans, especially groups that have been historically marginalized. The role or non-role that my biological ancestors played in creating that situation should not greatly impact my response. Compassion and desire for equality, not white guilt, should drive the discussion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey Alex thanks for your comment!

I’m sorry if it wasn’t as clear as I wanted it to be in the essay, but I don’t point blame at liberals alone for native genocide, slavery, and US imperialism, I just argue they share equal blame for them with conservatives, who many seem to blame exclusively. This is an important point for me, because I believe a sense of culpability among white Americans is more likely to engender action than a desire to let other groups gain an equality that they’ve been socially, politically, and economically taught is a threat to their own chances for success. It might just be my own cynicism, but I am more than willing to work in any direction that can effect my ultimate goal of reparations. If using history as a means of fostering compassion is a possibility, I am certainly open to it.

I also believe that the descendents of ethnic groups that have successfully assimilated as white after immigrating to the United States are as culpable as the descendents of earlier colonists. They were sufficiently aware of America’s history to know that the surest way to success in the United States was to become more ethnically palatable to native-born white Americans so that they might have the opportunity to benefit from the privileges of the racial hierarchies that greeted them nationwide upon their arrival. My father’s family served in Union militias in Missouri almost immediately after their arrival to the Unites States during the Civil War. But, their successes and those of their descendents (including me) is owed in part to the privileges of their eventual decision to assimilate as white. That decision represents a clear choice on their part to buy into a national history that they perceived accurately as privileging to white Americans.

You mentioned modern Germany, and I think that’s a good example of the power of reparations. After the war, the newly formed West German government began paying reparations to victims of the Holocaust and the state of Israel. The decision forced the issue of German citizens’ culpability for the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust into the public conversation and ultimately led to a collective sense in Germany that their nation’s prime role in international affairs was as the defender of global human rights.

Germany is also a good example of where I think the ultimate responsibility for reparations lies. I believe that, because the federal government not only defended genocide, slavery, and imperialism, it was built to advance those acts as goals towards its continued and expanded success. So, I believe that the federal government is responsible for ensuring proper reparations are made. I also think the federal government should be responsible for the establishment of an official truth and reconciliation commission, which proved effective in South Africa after Apartheid.

I will admit there are limitations. Because I believe the federal government and other national governments in countries with historical privileges (like the former metropoles of European empires) are responsible for reparations, the payment of reparations would be limited for practical reasons to the governments that are still currently in existence. No one can demand reparations from the Roman Empire because it no longer exists.

Because historical privileges in the United States and elsewhere were designed to promote the financial gain of those at the top of the social hierarchy, I believe that reparations should ultimately take a financial form. German citizens pay a special tax to pay for reparations, an annual reminder of the debt they owe. White Americans could just as easily pay a tax to fund reparations designed to more equitably share the financial benefits of American success with other citizens and the citizens of foreign countries in which the US interfered for its own self interest.

But, my post is less about reparations than it is about urging groups that refuse to acknowledge their role in the construction of our historical privileges to do so. My hope is that working towards that conversation might motivate Americans that benefit from historical privileges to search for any and all mechanisms capable of deconstructing those privileges and building a more equitable system.

LikeLiked by 2 people

While the Roman Empire is dissolved, many other seats of empires are not. Britain, France, Spain, Sweden, and others are alive and well. Should they pay reparations? To whom and for how long? Who should calculate it? Is there a statute of limitations on this sort of thing?

I think you are absolutely correct in admitting that there are limitations to this process. It seems that some confusion also arises from the nature of assigning responsibility for past crimes. I find it odd on the one hand that you tie it to governments/state on the one hand (and for practical purposes responsibility vanishes when the state is dissolved) and tie it to descendants and ethnicity on the other. Your example works in the German case, but seems to break down in the U.S. case.

As intrigued as I am by your idea, I don’t know that a tax based on skin color is the answer. That seems to lack a lot of nuance, but perhaps I shouldn’t seek to over-nuance everything. It’s the academic coming out in me.

Regardless, I doubt we will face this type of question in the near future. If we can’t get Republicans to raise taxes in order to pay for roads and bridges, I sincerely doubt we will get largely white politicians to legislate skin-color-based wealth redistribution anytime soon.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think you make a number of fair points here, Alex. I would add only that white US Americans have long denied that we are the beneficiaries of a violent history that favored our ancestors and favors us consequently. I believe that the “role or non-role that my biological ancestors played” in history matters to the extent that we need to wrestle with that history, period (especially for those of us whose biological ancestors did play a role). This is something I choose to do; nobody makes me. I think our society would be better off if more people did the same.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Corey- I think we are in complete agreement regarding all of those points. Some of my biological ancestors played an active role in Native oppression, some missed out on that opportunity because of their late immigration to the United States, but ALL benefited from their status as whites. This is something that troubles me on some days, makes me take action on others, and makes me consider agency and atrocity in the past on all of them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a complicated process, and it’s certainly not one I can figure out on my own. Determining the exact nature of reparations is something for our nation to determine collectively. That’s where Americans figure in as individuals. The US government is meant to be responsive to its citizens demands, and I think we as citizens should be fightung for the reparations process to begin, a demand our government might be forced to hear if we begin to act more collectively.

I also think that the individual citizens of other nations have a similar role to play. They should be pushing their leaders to open public discussions about potential reparations and those leaders should be pushing the international community to do likewise. The former European empires certainly owe reparations, and any financial redress paid to former colonies could serve as both an acknowledgment of parity between the global North and South and a platform from which nations in the global South might more effectively profit from internal and external economies. The Israeli economy enjoyed unprecedented growth because of the stimulation provided by German reparations.

In the United States, I think a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is the first step and might be at least partially responsible for determining the nature of that process after the conclusion of any hearings or investigations.

And, I agree that without ousting Republicans this conversation has no chance of turning into policy. In the short term, supporting the Democratic Party may be our most viable option for taking steps in the right direction. But, I’m also open to any other avenues for promoting change that present themselves.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nathan- I agree that ousting Republicans is a good start, even if the Democrats seems like an unsure goal in making real changes. Although I don’t know that I share your (seeming) support towards the Israeli state, I think that economic parity between the global North and South would indeed be a step in the right direction.

Finally, I share in your opinion that individuals citizens have an ape-like role to play. That mid-Atlantic snarl finds new verbal ammunition at every turn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My feelings toward Israel are complicated, largely as a result of my own Jewish heritage. But, I hope you don’t take my comments as support for or condonation of their actions toward Palestinians. Parity is an important goal to work toward in Israel, the United States, and the rest of the world, and I think we as historians have an important role to play in that process because global and local inequities are largely a result of historically grounded forces.

LikeLiked by 2 people