by Julia Feliz Brueck and Z. Zane McNeill

Woke up this morning / heart beating, inhale, exhale / will I die today?[1]

In 2017, ociele hawkins published a poetry collection, From the Dust We Rose. Her poetry was born from Black love in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement. As a Black nonbinary femme, ociele wrote about Black queerness and Black joy as resistance in the face of violence. With the uprising in Minneapolis provoked by the murder of George Floyd on my mind, ociele’s words echo the present:

It make you wanna cuss / them lies that say we be the ones that got the problem. / that nonsense that put blame on us for / them brutal centuries. These brutal centuries… / we in it how we been put in it: fucked up and strong. murdered / and innovative. brittle and soft. / now ain’t that some shit! Some sad ass shit! it’s sad. we beautiful. / i think so.[2]

As a millennial and a Gen Z, we have been born to centuries of generations that found it easier to ignore oppression against/the resistance from Black, Indigenous, Queer, disabled, and neurodivergent people. We grew up to live the reality of these intersections, and in recognizing “we in it how we been put in it: fucked up and strong…,” who we are is central to what and how we write, organize, and live in rebellion against the white heteropatriarchy. We recognize that despite our identities, we hold privileges and actively choose to recognize and work against “them lies that say” that George Floyd and #BlackLivesMatters “be the ones that got the problem.”

Zane considers themselves an activist-scholar. They write and research in order to understand the past, become a better activist, and make more impactful change in the world. As an activist-scholar, they attempt to use their platform in the so-called ‘ivory tower’ to uplift those voices, amplify their critiques, and archive their protests.

Julia accepted the label resource activist and although considered a scholar, was kicked out of an ivy league university by daring not to hide their multi-faceted identities, which form who they are and always have been. Unfortunately, individuality is reserved only for whiteness. Black, Brown, and Indigenous People are expected to perform community and adhere to a single stereotypical identity—the token. And yet, Julia unapologetically continues to attempt to unite their identities as an act of activism.

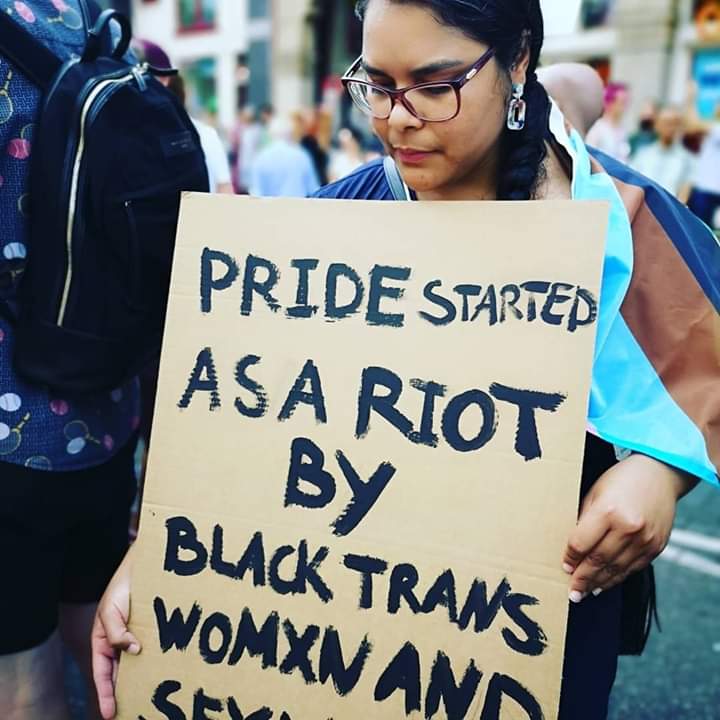

The collection Queer and Trans Voices is very much so the product of a complicated evaluation of our activism and the movements we both fight for/in/with from very different communities. Somehow, in attempting to disrupt two identities in common, we ended up finding commonality between even more communities, identities, and cultures across the globe affected and aware through the awareness of their own experiences as queer vegans—of Color and not. It shouldn’t have been as validating and surprising as it was since, as one contributor to Queer and Trans Voices, LoriKim Alexander, one of the original Co-directors of BlackCuse Pride, explains, Queers of Color have always been integral to all social justice movements. In her exploration of Black futurity, fabulation, and liberation, Alexander states, “Even when the LGBTQIA+ movements remained centered and focused on white Trans and Queer people,” with Queers of Color actively being pushed to the margins, “Trans, Nonbinary, and Queer Black and Brown People have always been here.”[3]

Queer and Trans Voices is a community project fueled by the belief that exploring the interconnections between social justice groups, building bridges between movements, and dismantling hierarchies between oppressed groups through consistent anti-oppression is a must. It raises critiques of the carceral system, neoliberalism, heteronormativity, white supremacy, and single-issue veganism. These evaluations hope to guide the movement to what it should be, which includes the futurity that embraces consistent anti-oppression can look like but, at its heart, the book outlines a way of living and expanding the boundaries of community. As Julia Feliz Brueck explained when they coined the term,

Racism, islamophobia, anti-Semitism, classism, transphobia, homophobia, ageism, xenophobia, sexism, body shaming, health shaming, and the list goes on do not belong in a movement that claims to want justice.

While humans from marginalized identities do not chose the latter as identities, the vegan identity is a chosen one. Importantly, despite their interconnections, which are seldomly recognized between movements, veganism/Animal Rights remains ignorant of its own role in racial justice work by also centering the privileged white majority in a movement meant to raise the voices of human victims. In essence, the movement that utilizes the same tools used by U.S. and European society, where history is erased and re-written. These invisible tools are easily invoked in spaces where a lack of racial awareness persists, and they are powerful because they ensure People of Color remain submissive and assimilate with the promise of safety that, as Black Lives Matter has illustrated, is a mirage that benefits whiteness over Communities of Color. Veganism/Animal Rights takes it one step further by indirectly continuing the direct oppression of marginalized communities, often animalizing People of Color while humanizing nonhuman animals.

In actuality, the same is true within all movements that continuously center the white perspective, as in veganism/Animal Rights, as well as the LGBTQIA+ movement, which allowed whiteness to highjack a radical fight for queer and trans rights led by Trans Black and Brown womxn only to gentrify it, as well as silence and ignore the disproportionate fight faced by its Founders of Color.

With whiteness and cooption of queer liberation in mind, Blu Buchanan’s work on Black trans fabulation comes to mind:

The everyday practices Black trans people undertake are revolutionary, in that they prioritize and celebrate Black trans life in the overwhelming face of Black trans death.[4]

This premise inherently inspires the work behind the collection. There is great power in archiving voices that have historically been eclipsed, marginalized, and erased. By looking into the past and archiving the present, we can create our own futures. By archiving, Zane means facilitating and documenting conversations and oral histories that center traditionally oppressed peoples. As McNeill has stated before in the Activist History Review, “I conceptualize ‘activist history’ as an inherently political position…Both of these words—‘activist’ and ‘historian’— inform each other. I could not be one without the other.”[5] Thus, giving LGBTQIA+ vegans, especially Queers of Color, a platform as an inherently activist position. This collection is a product of activist-history—by documenting our present we are archiving our voices for the future.

And so, we are forced to go back to the beginning—the very beginning—to understand how we got here, how nonhumans were exploited to oppress humans without consent, how they contributed to the erasure of queerness and Two-spirit people, and in essence, how the exploitation, aided by those themselves exploited, persists to this day. Today, we can witness the history of tomorrow while recognizing how the past got us here. While veganism seems disconnected in all of this, it is very much part of this story. It is one that we must become aware of and understand in order to begin to disband the hierarchies that place more value on some over others.

Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Julia Feliz is a resource activist, writer, illustrator, and educator with a focus on consistent anti-oppression advocacy. They are the founder of SanctuaryPublishers.com – a non-traditional, grassroots publisher working to build bridges and raise voices. Learn more about Julia via JuliaFeliz.com. You can support their work by donating here.

Z. Zane McNeill is a dirt queer from Appalachia fighting for y’all to really mean all. They are a genderqueer activist-scholar, socially-engaged artist, and 10-year vegan passionate about consistent anti-oppression work that uplifts the most marginalized within our communities. He is currently working on a community-building project raising queer voices in Appalachia, and establishing a collective guide on how to do activist scholarship/be an activist scholar.

Further Reading

[1] Hawkins, 22

[2] Hawkins, 24.

[3] Alexander, 267. Queer and Trans Voices : Achieving Liberation Through Consistent Anti-Oppression (2020).

[4] https://activisthistory.com/2019/05/17/the-regular-and-necessary-practice-of-black-trans-necromancy/

[5]https://activisthistory.com/2019/03/29/what-does-it-mean-to-be-an-activist-historian-a-roundtable-with-the-editors/

0 comments on “Activist Scholarship, #BlackTransLivesMatter, and Consistent Anti-Oppression”