There is a conversation about race that white families are just not having. This is mine.

I am a historian of race and labor in the American South. I study slavery and its aftermaths for working people—particularly African Americans—and the ways in which those in power—usually wealthy whites—exploited and abused them.

As part of a personal project, I recently began going through my family’s historical papers. I had initially asked for the papers when, at a recent holiday party, one of my friends told me that his great-great-grandfather had been on Sherman’s march. Mine, I replied, had died in 1865 fighting Sherman. In the awkward silence that followed, I conceded, “they had it coming.” I meant it. You cannot exploit and abuse millions of people for profit without consequences.

That conversation reminded me of the ominous-looking box that held miscellaneous documents from my family’s past. Having advised other families to donate their historical collections to archives, it seemed only right that I should find an appropriate home for my own. With permission from my father, I started cataloging our papers with the goal of eventually donating it to an archive in Georgia.

Seeing that box again reminded me of the family lore, passed down from my grandparents, that animated my childhood. Their stories revolved, like clockwork, around themes of extreme poverty, unscrupulous Yankees, and victimized white Southerners. Desperate for food after the war, my great-grandfather had apparently killed their last remaining cow and brought the meat in a wheelbarrow to share with neighbors. Decades later, one of those families paid an artist to paint my father’s portrait. These were, as the story went, hard-working victims of an unnecessary poverty brought on by greedy Northerners.

Absent from this family lore, though, was any mention of enslaved men and women, their struggles, or my ancestors’ crimes against them.

I spoke to my grandparents frequently about my family’s history. In fact, I credit my grandmother with my love of history, and I miss her dearly. She taught me how to love books, ask difficult questions, and pursue justice relentlessly. But the stories she told me were also woefully incomplete.

Our family histories need to explore racial capitalism—the state-sanctioned redistribution of wealth from black to white communities—and its expressions in segregation, racially-exclusive housing policies, white flight, mass incarceration and, yes, slavery.

It is not my family’s enslavement of African American men and women that I found shocking. Anyone who does this kind of work could have guessed as much. What I couldn’t believe (and still find troubling) is that everyone knew, but said nothing.

These are the types of conversations white families must have if we are to have justice in our country. Our family histories need to explore racial capitalism—the state-sanctioned redistribution of wealth from black to white communities—and its expressions in segregation, racially-exclusive housing policies, white flight, mass incarceration and, yes, slavery. The trouble is, we just aren’t having them.

Thomas Brown Horne

My great-great-grandfather, Thomas Brown Horne, enslaved two men, two women, and seven children on his plantation in Baldwin County, Georgia. The census lists one of them, a five-year-old girl, as “M”—the abbreviation for “mulatto”—someone of mixed-race ancestry. She is the only one listed this way and, while we cannot be certain, it is very likely given her age and antebellum enslaver practices, that she was born after my great-great-grandfather raped her enslaved mother. She would have been a year younger than my great-grandfather and namesake, William Levi Horne, who was born the year after Thomas’ marriage to Martha Butts. To tie these two births together: Thomas, with his wife surely exhausted from caring for his infant son, likely forced himself on one of the women he enslaved.

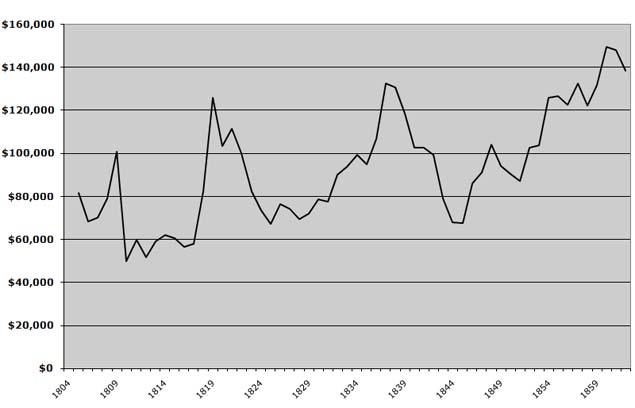

My great-great-grandfather’s enslaved workers grew twenty-four and one-quarter bales of cotton along with fifty-seven bushels of wheat, 600 bushels of corn, and fifteen bushels of oats. They also tended the 44 pigs, 20 sheep, 12 head of cattle, and four horses on the plantation that, together, cost $1200. These enslaved men and women, whose torture-induced labor made the Horne plantation worth $3000 in 1860, were by far his most valuable “possessions.” In 1860, they were worth roughly ten thousand dollars. Using a conservative conversion, they were worth $281,706.45 in 2017 dollars.

But because enslaved men and women were unwaged workers, their “value” to enslavers must also account for the expected returns on their labor. Their labor value to my great-great-grandfather would have been close to two million dollars in today’s currency.

We tend to think of enslaver elites as those having 50 or more slaves thanks to pro-Confederate mythology which defined the impact of slavery narrowly as part of its propaganda campaign. Generations of historians either sympathetic to or framing their debate around white supremacist claims that slavery wasn’t all that bad have perpetuated this myth of a small, hyper-elite enslaver class. For those of us less familiar with the scholarly debates, we see the myth of the planter aristocrat in movies ranging from Gone with the Wind to Django Unchained. It is a lie.

The eleven men, women, and children owned by my great-great-grandfather would have put him near the top 5% of white southerners in terms of wealth.

These planter elites did exist, of course, but they hardly represented slavery’s pervasiveness. And that is the point of the lie. It is meant to misrepresent the impact of slavery on American society. The eleven men, women, and children owned by my great-great-grandfather would have put him near the top 5% of white southerners in terms of wealth. The tales of a hardscrabble Horne existence in the Georgia piedmont were just that: tales.[1]

William Levi Horne

I did not know much about Thomas B. Horne growing up. In fact, until recently, I did not even know his name, though I heard countless stories about one of his sons, William Levi. When his father died in 1865, William was only eleven, and went with his mother and the rest of the family to live on her father’s estate.

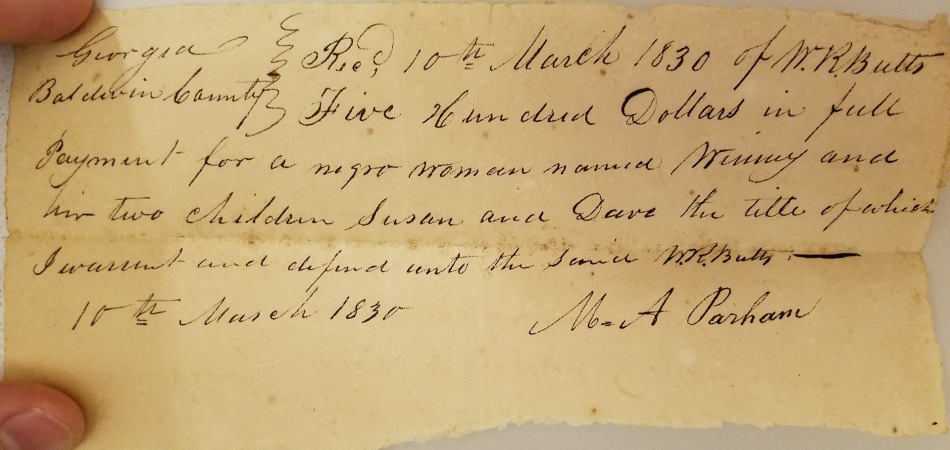

According to family lore, William R. Butts, Martha’s father, was something of a pioneer in 19th-century Georgia. When I was a child, I used to play with the telescope he had used “to watch for Indians.” “Uncle Billy Butts,” as the story went, traded with Cherokee Indians in 1820s Baldwin County before they were forcibly removed by U.S. troops in 1838. Their ejection probably enabled Butts, and later Horne, to acquire land more easily for their cotton plantations, made profitable through the unfree labor of enslaved African Americans. I have yet to find a “smoking gun,” but I’m fairly certain that Butts was a slave trader.

When William Levi (my great-grandfather) grew into adulthood, he was among the most prominent and powerful members of his community. He operated a profitable general store that, due to postwar lending practices, gave him significant leverage over his customers. Because there was little cash in the rural economy, farmers and sharecroppers would purchase goods on credit against their future crops. Lenders like William Levi frequently abused this relationship, charging exorbitant interest rates to ensure that debtors never quite made it.

He was also a justice of the peace, responsible for deciding small local criminal and civil cases, as well as a game warden, a position that also carried the ability to prosecute offenders. As a Jim Crow member of local courts and law enforcement, William Levi was part of a system designed to redistribute black property to white litigants while collecting fines and fees to benefit the local government and subsidize the taxes of white property-holders.

In this lies a crucial point: we need not make out our ancestors as monsters to understand how many of their actions were monstrous.

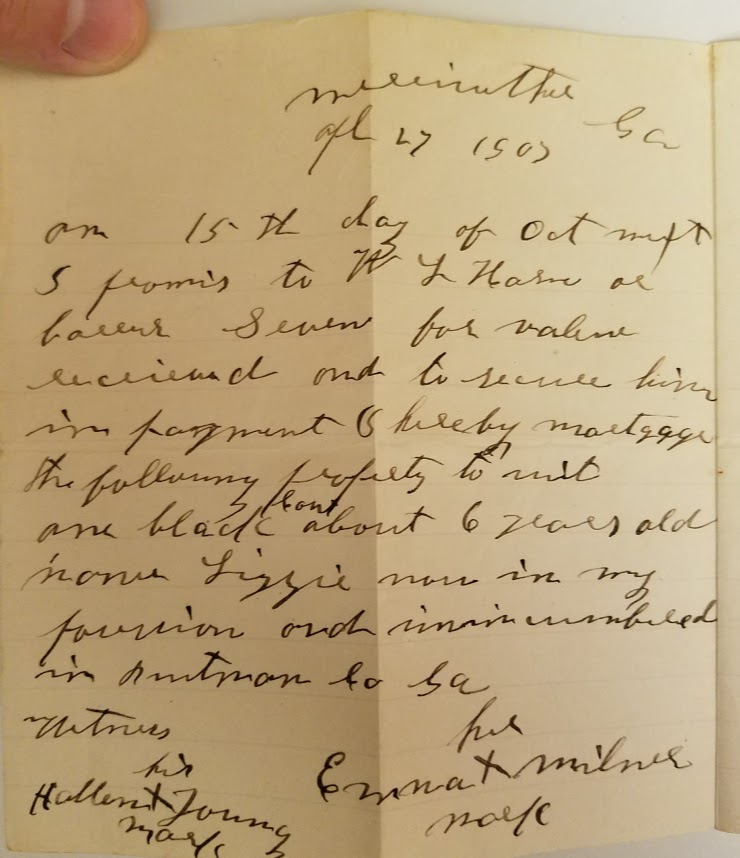

William Levi’s entrepreneurial and judicial occupations frequently overlapped. In one such instance, he helped execute a ruling against a black sharecropper, Burl Folsom. The court ordered the sale of Folsom’s property: “one bale of cotton, number 3966, weighing 391 lbs, in the ware house of Horne-Andrews Commission Co” along with all the seed, corn, and fodder he had. My great-grandfather not only helped execute the order against Folsom as shown on the court documents, but likely also profited from it by collecting fees for his judicial work and for processing the cotton from his warehouse.

Outcomes like this were incredibly common in a sharecropping system that, by design, prevented black workers from accumulating wealth. This system of racial capitalism combined state institutions that prevented black mobility with abusive white lending practices and the hyper-policing of African Americans. These institutions and practices helped white locals (especially the already-wealthy) to access wealth at the expense of African Americans. I feel certain that a close examination of the records would uncover hundreds such cases involving my great-grandfather.

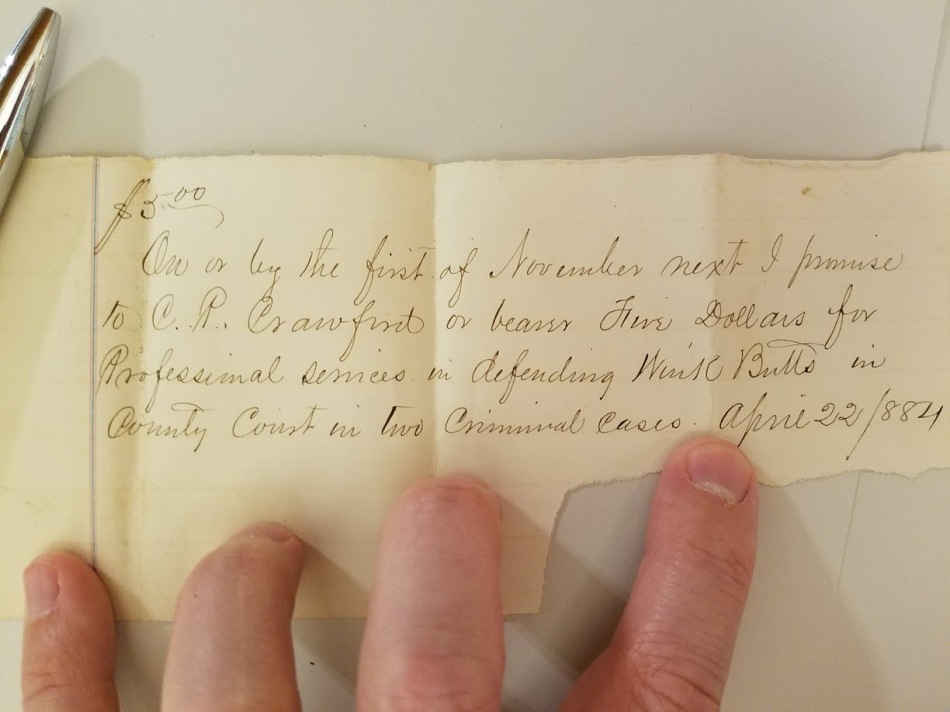

In another example, William Levi purchased a note from a neighbor for the legal fees of Wink Butts, an African American worker. Legal fees were a common way to compel African Americans to work without pay, and it’s quite likely that my great-grandfather used the note to force Butts to work for him. Notice, for example, that the debt would be paid to “C.P. Crawford or bearer,” indicating the frequency with which these debts were transferred. As the local justice of the peace, William Levi probably brought the initial charges against Butts himself, then benefited from the debt the charges caused.

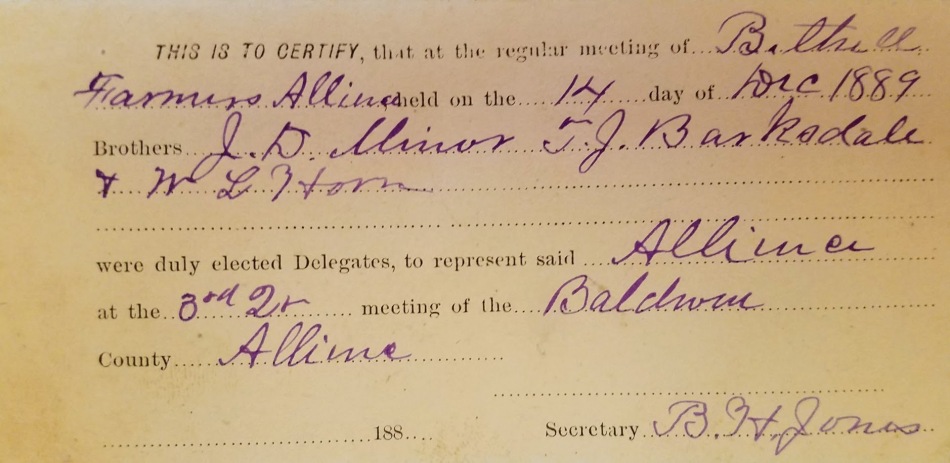

Though William Levi profited from lending to black farmers at unfair rates, he objected when the practice hurt white farmers. He was a leader in the Georgia chapter of the whites-only Farmers Alliance, which had been founded in part to force merchants and lenders to treat white farmers fairly. White landowners like William Levi pre-arranged wages and prices to ensure that black laborers would be unable to negotiate favorable terms. They used unscrupulous lending and legal practices to ensure that African Americans would never be able to get ahead. But when these very tactics were used on white workers, they cried foul.

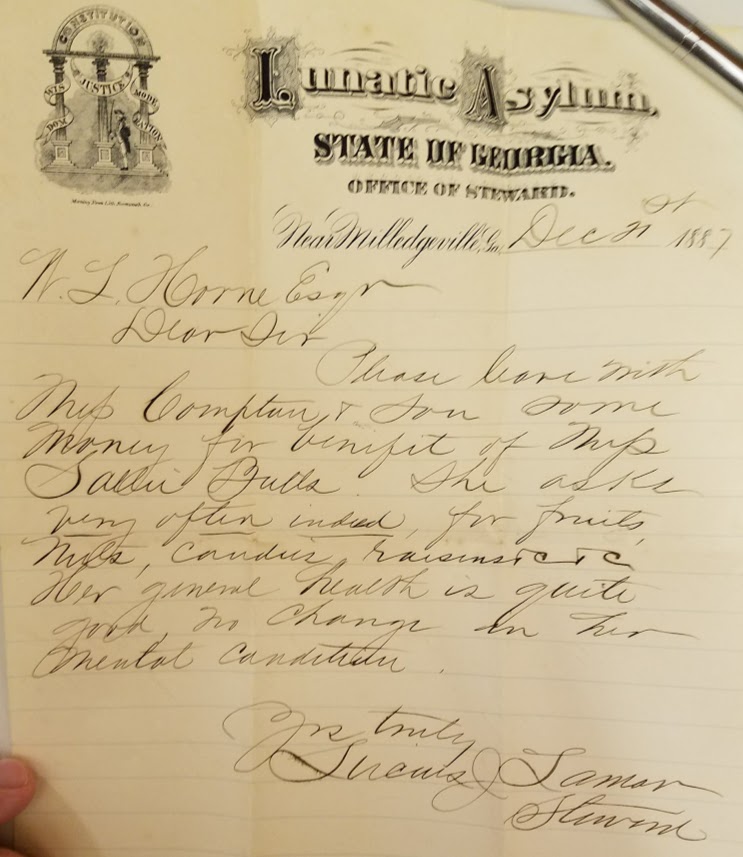

William Levi lost most of his wealth after a boll weevil infestation devastated his cotton crop, against which he had borrowed heavily to operate his general store. As my grandparents put it, William Levi was too generous with credit, and let family and friends take advantage of him. Having now gone through a fraction of the store records, I suspect that this was a veiled reference, at least in part, to Sarah Butts, his first cousin. Sarah Butts was apparently confined at the state insane asylum intermittently for the better part of thirty years. According to dozens of receipts and legal documents, William Levi supported Sarah from the time of her father’s death in 1881 through the early 1890s. And in this lies a crucial point: we need not make out our ancestors as monsters to understand how many of their actions were monstrous.

But, as researchers of wealth have long argued, this ending paints an incomplete picture of racial capitalism.

William Iverson Horne (that’s my name too)

My great-grandfather’s actions determined the options available to many within his community, none more so than my grandfather, William Iverson. My grandfather grew up without many of the privileges that accompanied his father’s status. In his telling, they had been destitute, a product of the unwillingness of their extended family to help them avoid foreclosure. And there was probably some truth to this version of events.

I never saw the bulk of what my great-grandfather owned, but I grew up playing with many of the valuables that had been in his house, and that now belonged to my grandfather. William Iverson kept the family silver, a Winchester long rifle, a collection of Confederate money, and some of their antique furniture. But these were hardly the most valuable assets his father left. His parents provided him with a good education in their home. Their former status probably also helped him make important connections. Together, these benefits helped him land a job in the whites-only post office, when so many others were out of work during the Depression. He would eventually work his way up to assistant postmaster. In this respect, his occupation was not too different from that of his father or uncle. William Levi had held countless jobs in local government, jobs that had required connections. In fact, Uncle Billy Butts had been appointed postmaster for Meriwether, Georgia before the Civil War. Perhaps it was just a coincidence. Perhaps.

We can probably skip over the state-sanctioned segregation that helped white baby boomers acquire education and wealth at the expense of their African-American neighbors. To be sure, this system of racial capitalism allowed me to grow up with greater access to wealth, city services, and social capital than many of my black friends. Actually, I found out as an adult that my grade school didn’t admit black students. The understanding was, apparently, part of the appeal for many parents. My success, however hard I work, is necessarily a product of that system.

When my own children are old enough, I intend to tell them where those opportunities came from and at what cost. We in white America are not as far removed from slavery (or Jim Crow, segregation, white flight, and mass incarceration) as we would like to pretend.

For me, it’s enough to say that my grandparents left me a little money to help me get through school. I’m incredibly grateful for that opportunity. Still, when my own children are old enough, I intend to tell them where those opportunities came from and at what cost. We in white America are not as far removed from slavery (or Jim Crow, segregation, white flight, and mass incarceration) as we would like to pretend.

I do not claim to have all the answers to the inequalities we inherited from our forebears, though a robust and meaningful system of redistribution would be a good start. Still, it’s important that we have these conversations as white families. We aren’t special or deserving because of our hard work; we’re privileged. The benefits of this privilege were drained from communities of color. That’s something, at minimum, that we need to discuss.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Notes

[1] Samuel H. Williamson and Louis P. Cain, Measuring Slavery in 2016 Dollars, https://www.measuringworth.com/slavery.php.

Further Reading

Edward Baptist’s The Half has Never Been Told examines the foundation of American capitalism in the everyday workings of slavery, while Keri Leigh Merritt’s Masterless Men looks at the impact of slavery on poor whites. Both show that my family’s wealth and power rested on their ability to exploit, not only the African Americans they abused and enslaved, but also on their coercion of their poor white neighbors. Edward Ayers’ Promise of the New South and Steven Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet both explain the sharecropping system and its relationship to politics in the post-Civil War U.S. south. They show how enslaving power, even after emancipation, was inter-generational and rested on access to state-sanctioned applications of authority in politics, law enforcement, and the courts. Finally, Tera Hunter’s To ‘Joy My Freedom investigates the experiences of African American women during the same period, and gives a good sense of what “M’s” life might have been like after emancipation.

Silence is golden in multiracial families even more so. All of my genetic and ancestral lines lead back to Virginia, not shocking as Virginia was the motherland of the enslaved.

My shock is when I found my 3x Great Grandfather, white confederate soldier, sitting in a photo with my black great grandmother, and their biracial children and grandchildren.

Stories are told theirs was a love story, but nobody answers where she came from and the beginning of their relationship.

Those biracial offspring married other biracial people, the same happened on m maternal lines, leaving me with a rainbow colored genealogy map. However, everybody screams “Native American”, dna says Ireland, Scotland, Russia, and a smidge of Native American. Interestingly, everybody knows stories of all our black relatives, but mute on our white forebears.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey Kevin, thanks so much for sharing your story. That silence is powerful, isn’t it? The photo of your great-great-great grandparents sounds really striking, and raises so many important questions, as you note.

It is amazing how complex each of our family histories is, how we grapple with similar sorts of awkwardness regarding our shared racial history, and the ways this produced each of us. I hope, and I get the sense you do too, that we can have more open discussions about who we are and how we got here. Regardless, I’m grateful you shared yours here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: From Steamship to Phonograph: Frederick Douglass, David Blight, and the Politics of Memory – The Activist History Review

Thank you for your work. It’s nourishing to take in all the research you’ve done and both your objectivity and subjectivity add to the recipe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I deeply appreciate the support and am so glad you enjoyed the essay.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this, these are the conversations that we must have in our white families. I refuse to keep quiet about my ancestors who enslaved power-less African Americans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

William Horne, how might in contact you? I am associated with a national organization that would benefit from hearing you speak, as well as our own UNC Chapel Hill. Can you contact me?

LikeLike

William, a fascinating and engaging article – thanks. I have only recently begun the exploration of family history and all the implications of that history in understanding the family role in slavery, segregation, and the obtaining of land. There is probably a family connection with you at some point since my ancestors were farmers in the Macon and the Atlanta areas. We had the family story that we were always subsistence farmers who barely made it, yet in the history I am uncovering there are records of slaves, land acquisitions that followed the removal of Native Americans, and of family members putting CSA after their signatures on documents even into the 1900’s. Thanks for sharing. Arthur M. Horne

LikeLike

Ah yes, the Macon Hornes were, if I remember correctly, large scale enslavers. I think they also operated a large business in town. Glad to see others doing the work!

LikeLike

Fine piece. Profoundly moving. Seen through the prism of the unrest and protest in the wake of police brutality in Minneapolis your essay asks for honesty as white america weighs the question of racial capitalism and systemic suppression of equal opportunity.

I am an outsider from India who has seen this in the form of caste system and untouchables in our society back home in India.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and I’m glad you found it useful!

LikeLike

Thank you for inviting the public to learn from your family history! You explain well how generational injustice has ripple effects to the present day. And how positions of status reinforce advantage at the cost of those deprived of status.

On my screen the last reading suggestion was incomplete…?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a similar story and just ran across yours. Mine even has a Sherman march. But mine concerns my JEWISH great-great-grandparents owning slaves–something most Jews don’t want to believe was possible. After I unearthed the history I broke the news to my extended family then did a radio show about it: https://soundcloud.com/tablet-magazine/well-be-here-all-night-part-2-slavery And I live in El Paso, TX, home of Beto O’Rourke. While he was stumping for President in 2019 he kept giving speeches to Black audiences saying that white people must tell their own families’ stories of slaveholding. From what I knew of his background, I suspected Beto was not confronting his own past, and I looked it up on Ancestry, then wrote this; https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jul/14/beto-o-rourke-slavery-ancestors-interview-family-tree

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the article. It has spurred me to have more open discussions within our expanded Horne Family regarding our family and slavery. I am visiting all of my Georgia cousins in January and this topic wiIl be at the top of the agenda for discussion.

I researched family history during the pandemic and the biggest surprise was that many of my ancestors were slaveholders, first in North Carolina and then in Georgia (Putnam, Pulaski, Dooly and Macon counties in Georgia).

Surprisingly, none of my siblings or cousins had ever heard that our ancestors were slaveholders.

None of the names of your Horne ancestors appear in my Horne Family history. However, there may be a connection. Would you be willing to share family history offline?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reaching out! My side of the Horne family split over some of the debts I mentioned in the essay and still aren’t on speaking term 130 years later, so I have little information other than what I’ve come across in the census. Hoping to do a deeper dive into birth and marriage records, but haven’t had the chance yet and didn’t get any hits from the low-hanging fruit. I’m glad to share anything that would be useful, and I’d be willing to bet that we Hornes are related somehow, but I’m sorry to say I don’t think I can be much help connecting the branches.

LikeLike