by Ben Railton

As an elementary school student in the Charlottesville Public Schools in the mid-1980s, I learned to swim from Mr. William Byers, a gregarious African American man who intimidated and inspired me in equal measure. Certainly it’s the inspirations that stick with me most, such as how he responded with compassion and care when a group of us watched the January 1986 Challenger launch (and thus explosion) together on a small TV in his poolside office. But beyond such striking individual moments, it’s also important to recognize that it was through Mr. Byers that I had these transformative educational experiences and learned this vital life skill.

Yet throughout his own Charlottesville childhood in the 1950s (he was born in 1946), and even into his adult years, Mr. Byers himself would not have been allowed access to many Charlottesville swimming pools, which like most pools and facilities across the Jim Crow South were segregated along racial lines. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 pushed first public and then private pools to desegregate, but private pools in particular resisted those legal mandates. Fry’s Spring Beach Club, the private pool across the street from my childhood home, only desegregated after it changed owners in 1968. Farmington Country Club, one of the most longstanding, prominent private clubs and pools in neighboring Albemarle County, maintained a controversial whites-only membership policy throughout the 1970s, adopting a non-discrimination policy only after members purchased the club in 1979.

All of the city’s public schools resisted desegregation for more than five years, supported by white supremacist officials such as U.S. Senator Harry Byrd and numerous members of the state General Assembly.

Moreover, and even more saliently, the same Charlottesville public school system that employed Mr. Byers to teach us to swim—and for which he worked for more than three decades until his 2014 retirement—was one of the last in the United States to desegregate after the Brown decision. All of the city’s public schools resisted desegregation for more than five years, supported by white supremacist officials such as U.S. Senator Harry Byrd and numerous members of the state General Assembly. The Assembly’s “massive resistance” bills gave Governor Lindsay Almond the authority to close any school where black and white students would attend together, and in the fall of 1958 he used that authority to close Charlottesville’s all-white Lane and Venable Elementary Schools for five months rather than admit African American students. All the city’s schools remained segregated throughout that school year, including Lane and Venable when they reopened in February 1959. That autumn, the first three African American students attended Lane High School, marking the start of integrated public education in the city. Although some Charlottesville public schools did not accept their first African American students for another year or two, the Supreme Court had ruled massive resistance unconstitutional in 1959, and the formal battle against educational integration in the city was over.

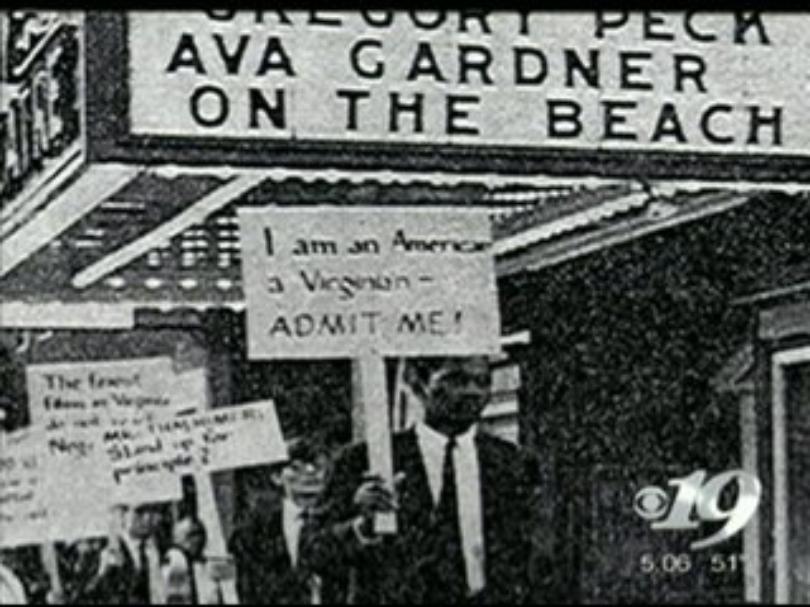

Charlottesville’s conflicts over segregation would continue for many more years, however. In late February 1961, a mixed-race group of students and activists attempted to integrate the University Theater, a whites-only movie theater operated by the Paramount Corporation and located in the University of Virginia’s popular “Corner” neighborhood. When the theater refused to sell tickets to the group’s African American members (the theater had no balcony and thus could not physically segregate its audiences), activists protested and picketed in front of the theater for three days. They were led by Virginius Thornton, the University of Virginia’s first African-American graduate student (and a co-founder of the national Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC), who marched with a sign that read “I am an American. A Virginian. ADMIT ME!” The protests garnered a good deal of attention and a front-page photo in the Daily Progress, but the University Theater remained segregated until after the Civil Rights Act passed on July 2, 1964.

An even more overt conflict took place two years later at Buddy’s Restaurant, a popular Charlottesville establishment that, like many in the city in the 1960s, served only a white clientele. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement’s sit-ins and demonstrations across the South, and supported by the local NAACP chapter, a mixed-race group of protesters led by community activists and ministers Floyd and William Johnson attempted to stage a sit-in at Buddy’s on Memorial Day in 1963. They were denied entrance to the restaurant and met with violence by white customers and counter-protesters; both Floyd and William Johnson were physically assaulted (Floyd had to spend two nights in the hospital), and other protesters including University of Virginia History Professor and Civil Rights ally Paul Gaston were likewise bloodied. The resulting press coverage caused a number of local establishments to voluntarily desegregate, but Buddy’s remained segregated until the Civil Rights Act passed—and then its owner Buddy Glover chose to close rather than desegregate.

Better remembering these and other histories and stories of segregated Charlottesville would both challenge and enrich our conversations about the summer 2017 protests and violence in the city. Perhaps the most important challenge would be to the narrative—one I’ve heard from many white Charlottesville residents, along with other media reports—that the 2017 white supremacist and neo-Nazi protesters are entirely “outsiders” to the city and its community, agitators who came to this place specifically for this particular occasion. That may be literally the case for many of the individuals who came to take part in the protests, although two of their leaders, Richard Spencer and Jason Kessler, did graduate from the University of Virginia and thus have been connected to the city (and to its histories of segregation and community) for many years.

It’s particularly important to remember that the Charlottesville public schools resisted desegregation far longer and more aggressively than most of their counterparts across the South.

Yet whatever the demographic make-up of these groups of agitators, the overarching idea that communal protests and battles over white supremacy and race are anathema to Charlottesville could not be further from the truth. Moreover, while some of those histories of segregation and conflict are of course representative of both the Jim Crow South specifically and America more generally in the 1950s and 60s, others were particularly acute in Charlottesville. For a city historically and thoroughly linked to the concept of inclusive public education—Mr. Jefferson’s University being one the nation’s first public and secular institutions of higher education, after all—it’s particularly important to remember that the Charlottesville public schools resisted desegregation far longer and more aggressively than most of their counterparts across the South. We must remember that for young African Americans like William Byers growing up in the city across these decades, many schools worked with special force—even closing for months and denying an education to all of their students—to keep young people of color outside of their communities.

Remembering the experiences of mid- to late-20th century Charlottesville residents and communities also offers an important addition to our conversations around the origin points of these 21st century protests. While the campaign to remove the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues from two downtown Charlottesville public parks has been driven in part by city councilors such as Kristin Szakos and Vice Mayor Wes Bellamy, another prominent argument for removing the statues came from Charlottesville public school students of color. Zyahna Bryant, an African American student at Charlottesville High School (my own alma mater), organized a March 2016 change.org petition to the City Council requesting that the Lee statue in particular be removed. Bryant and hundreds of her high school peers (along with many other Charlottesville residents) signed off on the statement, which reads in part, “As a younger African American resident in this city, I am often exposed to different forms of racism that are embedded in the history of the south and particularly this city. My peers and I feel strongly about the removal of the statue because it makes us feel uncomfortable and it is very offensive. I do not go to the park for that reason, and I am certain that others feel the same way.”

Bryant and her peers provide a vital through-line between the late 1910s/early 1920s era of the statues’ construction, the 1950s and 60s era of segregation and desegregation conflicts, and these unfolding 21st century histories and debates. It’s not simply that many older Charlottesville residents of color such as William Byers grew up in segregated Cville, affected and circumscribed and too often defined by how its theaters and restaurants, pools and schools categorized their communal identities and roles. It’s also, and just as crucially, that the city’s younger residents of color live in and around spaces that echo, reflect, and even embody those histories of racial segregation and white supremacy.

If we’re going to engage successfully with 2017’s histories of race and violence in Charlottesville, we had better collectively listen to the voices and stories from across those generations.

Those spaces aren’t always as overt as statues to Confederate leaders, but they’re everywhere. For example, Charlottesville High School, which was built in the early 1970s to be the city’s first integrated-from-the-outset high school (when Lane proved too small to accommodate an integrated student body), features courtyards watched over by windowed guard towers and separate wings that can be isolated by metal gates that descend from the ceiling. I’ve never been able to find documentation that these elements of the school were modeled on a prison, but that’s certainly how they felt to me as a student there in the early 1990s—and I can only imagine how they felt to the first generations of African American students to attend, or feel to Bryant and her peers today.

If we’re going to engage successfully with 2017’s histories of race and violence in Charlottesville, we had better collectively listen to the voices and stories from across those generations. Of the young men and women who integrated the public schools, the protesters who picketed outside the University Theater and Buddy’s, the teenage and adult activists who continue those historical battles in Lee and Jackson Parks today. And of Mr. Byers, who grew up unable to attend most of Charlottesville’s public schools and yet went on to become one of the most enduring and important presences—for so many students and generations, and for me in particular—within that shared, fraught, defining Cville space.

Ben Railton is Professor of English Studies and Coordinator of American Studies at Fitchburg State University. He is the author of four books (most recently History and Hope in American Literature: Models of Critical Patriotism), the daily AmericanStudies blog, and numerous pieces of online public American Studies scholarship for sites such as HuffPost and the Washington Post‘s Made by History blog. He’s also the Boston chapter leader for the Scholars Strategy Network and an advisor for the American Writers Museum.

Ben Railton is Professor of English Studies and Coordinator of American Studies at Fitchburg State University. He is the author of four books (most recently History and Hope in American Literature: Models of Critical Patriotism), the daily AmericanStudies blog, and numerous pieces of online public American Studies scholarship for sites such as HuffPost and the Washington Post‘s Made by History blog. He’s also the Boston chapter leader for the Scholars Strategy Network and an advisor for the American Writers Museum.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Pingback: Mapping White Supremacy – The Activist History Review

Thank you for this open-minded and compassionate article. I found it while researching for a book I am close to finish writing and publishing. My story is part memoir and part fiction and deals with the same themes here…looking to the past from all perspectives to understand why we are in the circumstances of today and how we can do better. My story takes place where I grew up in MD and learned more about family roots in VA tied to the Confederacy in the Civil War. The White Nat. rally and violence and Heather’s death in Cville prompted my story. Planning to publish in Jan. 2018.

Again, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just saw this comment, Perri. Thanks so much, and I will look for your book!

Ben

LikeLike

Pingback: Editors’ Pick: Our Favorites from a Year of #ActivistHistory – The Activist History Review

Such an informative post!

LikeLike

I came across this compelling article when I was trying to find out when The Virginian restaurant desegregated (I saw a recent piece on how 2023 marks its 100th year on “the corner”).

My father, who is still alive at 88, was on the school board at the time when the new high school (I’m CHS class of ‘81) was proposed. He could tell you for hours as to how that all went down.

Paul Gaston was our neighbor and even as a young kid I knew of his efforts to bring about equality in Cville. In fact, when my parents bought their house there, they were asked to sign a CC&R that would not allow resale to non-whites (and other such language). My father would not sign it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Considérer l’histoire : l’histoire très américaine des piscines publiques - VueLavie