by Zayad Bangash

When asked to examine the Netflix series The Crown‘s portrayal of decolonization I was intrigued. The show focuses on the early reign of Queen Elizabeth II and how she establishes herself as the first female monarch since Queen Victoria. The contradictions between these two monarchs are striking. Queen Victoria took the throne as Britain began some of its greatest internal and external expansions. Elizabeth, on the other hand, took over an Empire that had recently lost its main ‘jewel’—the British Raj—while domestically British industry and trade were reeling from the devastation of World War II. The show reveals these stresses subtly over the course of the first season. In the third and fourth episodes, brief comments allude to the necessity of continued rations seven years after the war, with special reference made to the ‘excesses’ of having a champagne toast in 1952. The British Empire was cash-strapped after spending much of its fiscal reserves fighting Nazi Germany, though that did not prevent it from attempting to maintain its empire or secure a place as a global player.

When looking over the episodes it is important to recognize The Crown is not about decolonization directly, it is fundamentally a drama about internal palace tensions and the Queen’s relationship with her people and government. The show is telling a story of a world, a Britain, a royal family, and a young couple all going through a period of amazing social transition.

Decolonization as a global phenomenon took place in waves following World War II. The British Empire had not only exhausted its financial capital during the war but its political capital in the colonies as well. Desperate for support, promises were made and excessive demands were placed on its colonial subjects. British India raised over two and a half million combat soldiers and become a major base of operations for the Allies in their efforts against the Japanese in South East Asia and China. The African colonies, especially Kenya, offered over a hundred thousand soldiers and thousands of laborers. As a result, the war demands helped shatter the illusion of a British ‘civilizing mission’ and after the war many in the colonies could only see colonial exploitation.

While interspersed with flashbacks, the show is very much focused on the period from 1952 to 1956, a period between two major waves of decolonization. As mentioned, 1947 saw the end of the Raj, but that early period also saw the end of British rule in the Middle East and parts of Asia. The year 1960 would mark the next wave as more African and Asian colonies gained independence. In terms of the show, the period covered should have been fascinating. This was a period when the Crown was faced with increasing pressure from areas still under colonial rule and was forced to deal with new and non-white dominions and independent states for the first time. So does The Crown do a good job on discussing or portraying decolonization?

When looking over the episodes it is important to recognize The Crown is not about decolonization directly; it is fundamentally a drama about internal palace tensions and the Queen’s relationship with her people and government. The show is telling a story of a world, a Britain, a royal family, and a young couple all going through a period of amazing social transition. When watching the show I looked for discussions involving key words of decolonization from the period like ‘empire,’ ‘imperial,’ ‘independence,’ ‘colony,’ and many others. I will go through the key characters and places I found most connected to the ideas related to decolonization and then I will conclude with a final verdict on where decolonization fits in The Crown and whether the show is giving it its proper due.

Lord Mountbatten, a.k.a. Uncle Dickie

The Crown starts off pretty promising in terms of decolonization. In the very first scene we begin with Elizabeth’s wedding to Prince Philip of Denmark and Greece in November 1947. At the wedding, Winston Churchill mentions to his wife that the whole marriage was “engineered” by Philip’s uncle, Lord Mountbatten, adding that Mountbatten was also, “the man who gave up India.” This is a reference to three months earlier when Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, oversaw the end of British India and the bloody birth of India and Pakistan. As an American of Pakistani descent, it was a little amusing to hear Mountbatten despised in London in a way similar to how many Pakistanis view the last Viceroy of India today. Many in both India and Pakistan blame him for the bloodbath of Partition, and Pakistanis in particular view him as biased to India’s demands at Pakistan’s expense. The August 1947 Boundary Commission’s controversial decisions to draw partition lines that left Muslim areas of Punjab in India and cut off what became East Pakistan with its industrial hubs and resource markets—combined with Mountbatten’s push for Kashmir to join India—still anger many Pakistanis today. For many across South Asia, Mountbatten’s actions are blamed for the brutal violence of Partition and even a recent attempt to rehabilitate his role in film has faced stinging, articulate backlash from South Asians. More damning is the alleged affair between Mountbatten’s wife Edwina and India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which many also attribute to Mountbatten’s alleged pro-bias to India (although there still exists no actual proof an affair actually occurred). In episode 5, “Smoke and Mirrors”, Edward VIII directly references this alleged affair while making fun of Lord Mountbatten to his guests.

More interestingly, I am not sure if people in Britain saw Mountbatten as the guy who messed up keeping India as the show implies. The fact that he was appointed to the job in February 1947 to replace a viceroy who was moving too slowly in arranging the British withdrawal seems a fairly obvious indication that his sole objective was getting Britain out of India as quickly as possible. The one question the show seems to ignore is Winston Churchill’s role regarding India. Mountbatten oversaw the bloody Partition but Churchill can certainly be blamed for starving Bengal during World War II. The evidence of his complicity in the mass starvation would not surface until the work of historians in recent decades. The British denial policy and the full extent of the mass starvation strengthened Indian nationalists and hardened anti-colonial sentiment across India. If anyone was to blame for India’s ‘loss’ in 1947, a good amount of blame lay on Churchill for his wartime policies, as well as the extreme political, economic, social, and military demands placed on India’s population during the war. These hardships helped strengthen and cement anti-colonial sentiment to the point that after the war, many leading nationalists rejected anything less than full sovereignty.

Lord Mountbatten appears periodically throughout the first half of the season as a savvy palace actor attempting to usurp the crown from the Windsors. This comes off clearly in episode 3, “Windsor,” when Mountbatten pushes his nephew Philip to make sure his children take his name and not their mother’s. The show makes Philip’s beloved Uncle Dickie quite villainous as he toasts in his dimly lit castle—almost like Dracula. Overall, the show not only does its best to portray poor Uncle Dickie as openly scheming for power, but also makes a point of airing all his dirty laundry and scandals. It is important to remember that Lord Mountbatten was one of Prince Philip’s closest confidants and Prince Charles himself would later see Lord Mountbatten as his favorite mentor. I would be interested to see how or if the show will portray this as the years move on, especially since young Prince Charles so far has come across as a bit meek. The show’s most telling line about this relationship comes in episode 3 when Elizabeth tells Philip their children will not take his name and his response: “Am I the only man in the country whose wife and children don’t take his name? You can’t do this to Dickie.”

Winston Churchill

While Lord Mountbatten’s appearance in the show gives us a major character from the first major wave of decolonization, Winston Churchill ends up representing the imperial old guard. Britain may have lost major territories and remained in a precarious economic situation, but for the old guard it still had an important place in the world. Throughout the season, Churchill is obsessed with geopolitics and how Britain can influence them. We see him sitting in a tub, smoking a cigar in episode 2, “Hyde Park Corner,” asking through the door for Venetia to tell him if anything came from the foreign office, not showing interest in domestic economic papers. In episode 4, “Act of God,” while London is dealing with a devastating smog, Churchill spends his meeting with the Queen telling her and audience about Egypt and the Suez Canal. Here we see Churchill articulate some of his vision of Britain’s influence in the world. The Suez Canal cannot be lost; Churchill recognized its strategic location in the increasingly important geopolitical region of the Middle East and viewed its retention as a key piece in his argument that Britain remained a relevant, global power. It takes the tragic death of his favored secretary Venetia to prompt him into action about the smog.

It is in episode 7, “Scienta Post Ent,” however, that Churchill explicitly lays out his vision for post-World War II Britain. Churchill attempts to play the great diplomat and seeks to arrange a conference with the Americans following the first Soviet hydrogen bomb test. In his meeting with the Queen, Churchill discusses how Britain must ‘guide’ the United States to become a great power. On the surface, this appears a pragmatic vision, Churchill is carving a supporting role on the global stage for Britain. However, by assuming the role of mentor and guide to the United States and as a bridge to the Soviets, Churchill reveals an exaggerated sense of importance in his own capacity and that of Britain. It is very fitting and ironic this plan falls through because both Churchill and his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden suffer health crises preventing the meeting. It is symbolic that the British old guard is physically failing while the empire does geopolitically. Churchill understands the diminished position of Britain but he refuses to accept any role less than a major global actor.

Churchill sees in the new Queen a vibrant symbol of British global prestige. Throughout the season he emphasizes how important it is for her to maintain the regalia and symbolic power of the throne. In episode 8, “Pride and Power,” Churchill has to deal with news of anti-colonial unrest in Gibraltar and is faced with the decision of whether or not the Queen should continue with plans to visit there. While some suggest the trip be postponed, Churchill strongly emphasizes the importance of the crown as a symbol and pushes for her to visit. In a revealing conversation with the Queen before her departure he strongly emphasizes the importance of the crown as a symbol. He tells her, “…the cameras, the television. Never let them see that carrying the Crown is often a burden. Let them look at you but let them see only the eternal.” In the end, through a news telecast we learn the Queen’s trip to Gibraltar was a huge success. In the show, Churchill often acts not just as a symbol of the old guard and British prestige but also as an instructor to the Queen on global politics and Britain’s place in them.

Prince Philip

Where Churchill is the audience’s anchor to the old guard view, Prince Philip represents the modern, realist view. Throughout the season, Philip clashes with both the old guard and traditionalists in the palace. He immediately recognizes the moment Britain is in and pushes for his wife to be not just a traditional symbol of British prestige, but also a symbol of a changing British world. In episode 2, “Hyde Park Corner,” Philip finds the Kenya visit to be almost a joke. He teases the dignitaries he meets and finds the reverence in which he and Elizabeth are treated with by the local population to be ludicrous and excessive. He challenges the royal traditionalists in his battle over whether his children take his name. The old guard reacts with fury in episode 4 after Philip decides to take flying lessons (Churchill going so far as to have parliament discuss the issue, much to the disgust of Philip).

20 years ago, Britain had influence and control over one-fifth of the world’s population. You look where we are now in India, Pakistan, South Africa, Iraq, Jordan, Burma, Ceylon: all independent. But nobody wants to face it or deal with it, so they send us out on the Commonwealth roadshow. Like giving a lick of paint to a rusty old banger to make everyone think it’s all still fine. But it’s not. The rust has eaten away at the engine and the structure. The banger is falling apart. But no one wants to see it. That’s our job, that’s who we are.

In episode 5 Philip successfully persuades a reluctant Queen to televise her coronation, against the wishes of the royal traditionalists. Philip’s experience as a young prince who lost his crown because of popular resistance drives him to push the Queen to not lose touch with her own subjects and people. He pointedly claims he does not want to see the people kill the entire royal family and insists the crown must be aware of its context and the desires of its people. More importantly, he notes that involving the people through television democratizes the ceremony and includes the people—a potent idea in a time when across the globe colonized subjects were banging on the gates of their colonial overlords for not just a seat at the table, but control of their own destiny. Philip’s efforts democratize the process not just for the British people but for its subjects as well, giving them a sense of belonging to Britain’s most powerful symbol.

Episode 8 is wonderful in that it gives us Churchill’s articulation of the crown’s role and power in this new world while Philip offers a scathing critique. Philip is not an anti-imperialist but he is a realist of the actual condition of Britain and the limitations of the crown. While being fitted for a uniform, Philip for the first time reflects on the reality of a declining British Empire: “20 years ago, Britain had influence and control over one-fifth of the world’s population. You look where we are now in India, Pakistan, South Africa, Iraq, Jordan, Burma, Ceylon: all independent. But nobody wants to face it or deal with it, so they send us out on the Commonwealth roadshow. Like giving a lick of paint to a rusty old banger to make everyone think it’s all still fine. But it’s not. The rust has eaten away at the engine and the structure. The banger is falling apart. But no one wants to see it. That’s our job, that’s who we are.” His bitter assessment is a nice contrast a later episode when Churchill discusses the crown’s role as an eternal symbol to the Queen. Phillip is the realist who recognizes the power of decolonization and the importance of the crown and Britain to be ready for this new world.

Kenya

Episode 2, “Hyde Park,” is the show’s only major episode set and focused almost exclusively on a colonial space. Elizabeth and Charles are completing the commonwealth tour for the King in 1952 with their first stop in Kenya. The opening scene does much to emphasize visually the tension of decolonization. Elizabeth looks and speaks awkwardly as she addresses local British civilian and military leaders perched on a stage, while local African notables sit below in traditional garb. As Elizabeth praises the Kenyan capital’s modernity, she scans the dusty runway to see the crowd of traditional local people, many nude as they watch the Princess speak. After the speech, the governor introduces the royal couple to the local African dignitaries. Here the show gives us a Mau Mau Uprising easter egg. Elizabeth meets Senior Chief Waruhiu wa Kung’u of the Kikuyu, whose pro-British association would lead to his assassination a few months later, which contributed to the state of emergency declared in Kenya only a few months after the royal visit. As the governor tells Elizabeth how important the support of local leaders is to countering independence activists, Philip begins to tease these men. The faces of the notables are quite revealing as they silently express their surprised and hurt feelings to Philip’s conduct, especially when he jokes that one of the dignitaries had stolen a medal. Yet they are unable to vocalize this displeasure due to the power dynamics of colonial rule.

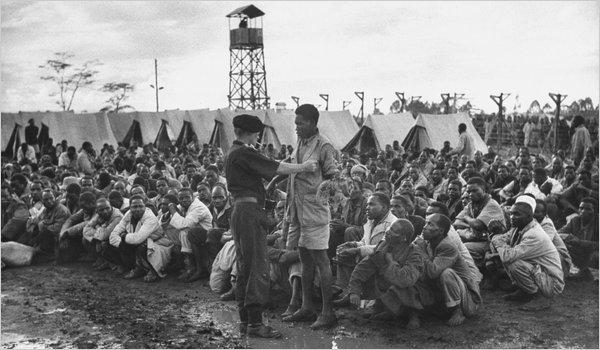

At a dinner later in the episode, Philip is amused at the deference, care, and even fear locals show them. They both smile that the locals fail to see them as normal people, but ultimately Philip and Elizabeth fail to comprehend the disproportionate power over the colonized they possess. A bemused Philip notes, “Why does everybody think, just because we’re royal, we like fine dining? Don’t they realize we’re savages? Good for nothing but school dinners and nursery food.” The director’s use of nonverbal cues from the African cast and extras really hammers home this point. I thought it was quite strange not to mention in a post-episode note that the Mau Mau Uprising occurred only months later (and, more importantly, that many Kenyans would be put in detention camps and suffer immensely in the ‘dirty war’ which occurred, especially since they did not mind doing something similar in episode 4 about the London Smog). Even some news report or expositional talk during the Prime Minister’s meetings with the Queen could have been done. Overall the show’s failure to portray a lasting royal impact on Kenya is quite the contrast from what happens in episode 8 when the show goes out of its way to tell us about the Queen’s success in Gibraltar.

Egypt

Throughout The Crown’s first season, Egypt increasingly becomes the principle decolonization site of the show. During episode 4, Churchill mentions the rising tensions and the importance of Britain’s control of the Suez Canal. In episode 6, “Gelginite,” Philip watches a photojournalist give a presentation on the 1952 Egyptian Revolution at a rowdy Lunch Club meeting. The audience of the slide show are initially chuckling and teasing but once he shows the revolutionary leader Gamal Abdel Nasser and the aftermath of anti-colonial riots, the reaction is beautifully captured. Silence and sullen faces replace the smirking and chuckling as the gravity of decolonization strikes close to home for this group of elite British gentlemen.

Since The Crown comes from the British elite point of view, the British perspective on Nasser’s actions come off to them as irrational and overly emotional. These are both classic imperial stereotypes used to delegitimize non-European intelligence and justify European imperialism.

It is the season finale, “Gloriana,” where the Egypt setup finally comes to head. Anthony Eden narrates to the Queen his visit to Cairo and a series of insults perceived by Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser. The filming of these scenes and the cutbacks to Eden’s flashbacks are done in a very engaging way. The casting of Nasser is excellent, but similar to Mountbatten’s characterization in the show, he comes off as quite the villain (but, then again, this story is told from Eden’s perspective). Yet the show never once shows us a picture or shot of the famously smiling Nasser. In terms of decolonization, what we see here is the British engaged with a former colony ostensibly as equals. The insults described are dismissed by Eden and Elizabeth both as minor and innocent hiccups. Both make assumptions about protocols and understandings that were universally understood in Britain and the Empire but not in this new world of independent states. For instance, Eden says an invitation to dinner in Cairo to Nasser implicitly meant it would be formal wear but Nasser shows up in his uniform, not informed explicitly that it would be a formal event. Later in the dinner, Eden compliments Nasser’s medals but Nasser recognizes Eden is being condescending. It is telling that Eden has not really bothered to take stock of Nasser, perhaps due to his overmedication and perhaps also his experience in the world in which the only right way was the British way. Since The Crown comes from the British elite point of view, the British perspective on Nasser’s actions come off to them as irrational and overly emotional. These are both classic imperial stereotypes used to delegitimize non-European intelligence and justify European imperialism. The show ends its portrayal of affairs in Egypt, along with Elizabeth and Philip’s relationship on a cliffhanger, setting both up for next season.

Verdict

Empire and decolonization often show up very briefly and usually limited to a scene, with the exception of episode 2 and episode 10. Most of the conversations are also expositional, i.e. Churchill explaining Egypt’s importance to the inexperienced new Queen or Prince Philip viewing a presentation at a lunch club. Churchill and George VI both espouse the importance of the symbolism of the crown, especially as a force of unity. This theme is confirmed throughout the series by expositional news reports, especially in episode 8 on Gibraltar and the Queen’s triumphant visit. Yet in the period presented, unity is simply not the reality for many of Britain’s colonial subjects. The show’s decision not to tell its viewers at any point, even in the background, that there was a brutal colonial dirty war going on in Kenya was disappointing. Such a portrayal actually would have served nicely to as a stark contrast to the show’s depiction of the Queen’s success in Gibraltar. I know public knowledge of Kenya was limited, but it would not be a stretch for the Prime Minister to mention it in one of his meetings with the Queen.

In The Crown, decolonization ultimately plays third fiddle to family drama and domestic political tensions.

Nasser and Mountbatten both come off a bit villainously and it so happens both were looked down upon by the royal family. Mountbatten becomes a dangerous schemer while Nasser becomes almost an anti-colonial caricature by the end, which makes sense considering from whose perspective we are viewing the events. Poor Uncle Dickie also has his dirty laundry aired by Edward in episode 5, while the show characterizes his close relationship to Philip as almost manipulative and controlling. In episode 3 we even learn Mountbatten pushed Philip to join the navy for the social contacts available through it. I will be interested to see how this relationship is portrayed in the next season and if we will see more interactions between the young Prince Charles and Mountbatten.

In general though, decolonization is really just expositional in most of its limited scenes (primarily to set up the Egypt crisis), and I would have faulted the show with a lot more had it not been for episode 8. This is where we hear Philip deliver his contemptuous critique of both the old guard and the crown’s role, letting the viewer see past the façade of British greatness presented by Prime Minister Churchill throughout the season. In The Crown, decolonization ultimately plays third fiddle to family drama and domestic political tensions. The show at least attempts to reach out to one of the most important global trends of that time period. As Britain enters its next wave of decolonization during the second season I hope we will get a much better sense of how the Queen adapts to these new developments and the new relationship between the royal family and its now former subjects. It was disappointing that so often in this season we saw the palace traditionalists smugly assert the traditional prerogatives over modernizers, but we never see them scrambling to figure out how to spin positively why the Commonwealth accepts members like India despite it not recognizing the monarch as head of state after becoming a republic. How do they explain or conduct royal protocol when non-European heads of state now visit the palace? This would have been an excellent angle to really emphasize how the world was changing and its consequences in the palace itself and was a missed opportunity for this season. The decision to ignore the Mau Mau Uprising was the most egregious omission. I hope that as the show chronologically moves towards a new wave of decolonization, The Crown will explore this momentous global phenomenon in detail.

Recommended Books on the topics discussed in this article:

Shameful Flight by Stanley Wolpert

Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire by Alex von Tunzelmann

History of the Hanged by David Anderson

Islands of White by Dane Kennedy

Churchill and the Islamic World by Warren Dockter

Ends of British Imperialism: the scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization: collected essays by Roger Lewis

The Empire Project by John Darwin

Zayad Bangash is a PhD student in history at the George Washington University, focused on modern South Asian history. He plans on focusing his dissertation on the intersecting social, institutional, and economic forces struggling for education in post-colonial Pakistan. He can be contacted at here.

Zayad Bangash is a PhD student in history at the George Washington University, focused on modern South Asian history. He plans on focusing his dissertation on the intersecting social, institutional, and economic forces struggling for education in post-colonial Pakistan. He can be contacted at here.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Zayad a very good coverage..Very informative and I learned many new things. Keep up good work and wish you success .

LikeLike

Pingback: Unit 12: Essay Plan & Research – Ealish's Blog 2